This Picture Book Helps Refugee Kids Integrate at School

When a kindergarten teacher couldn’t find the stories she was looking for, she wrote her own.

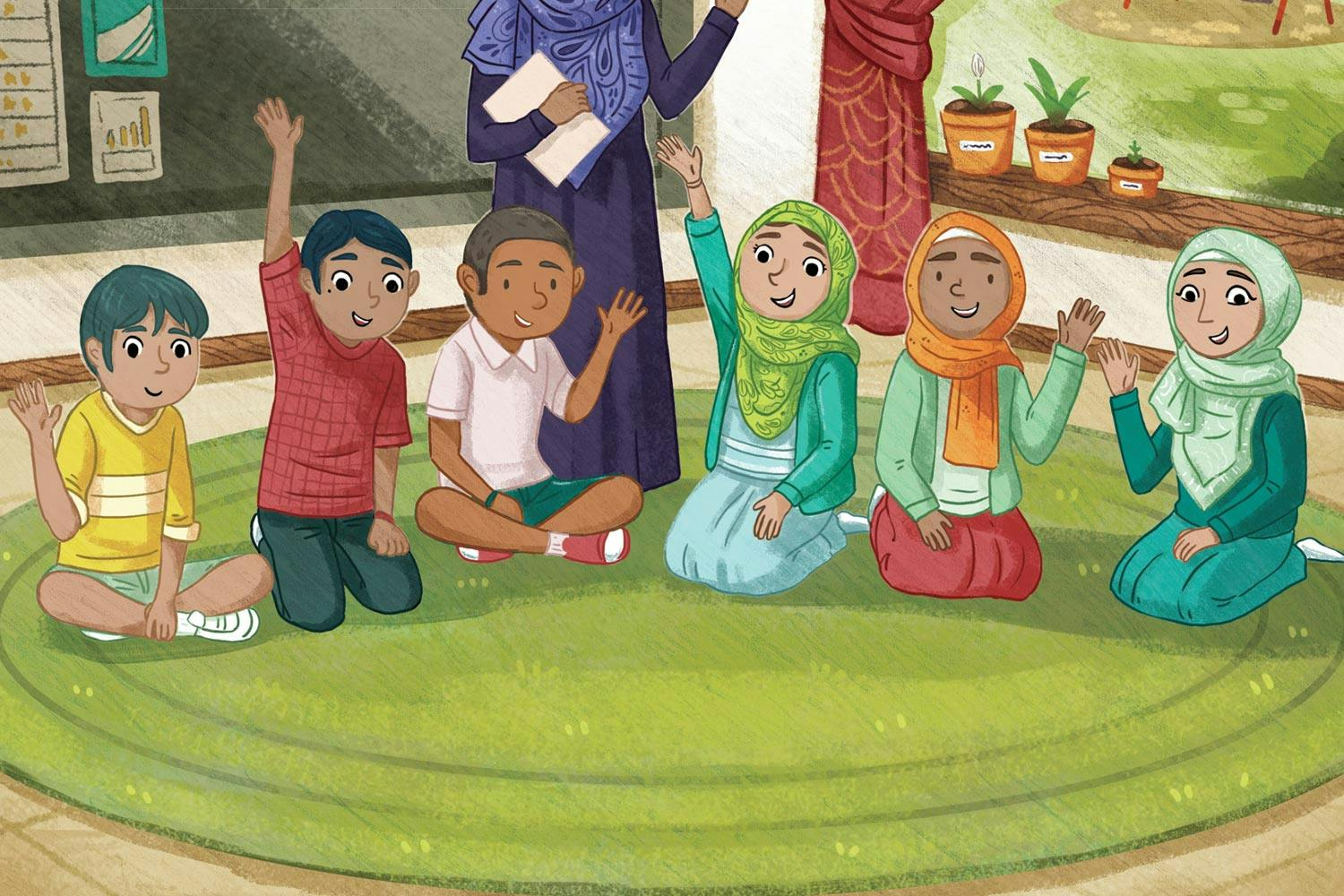

Detail from the cover illustration of Back Home

One morning at the elementary school in Delta, BC, where Shaista Kaba Fatehali teaches, the principal came to tell her she’d be getting a new student. Fatehali asked his name so she could label his cubby. It was Ahmed; he was a refugee from Syria.

“In my school,” says Fatehali, “we’ve had such an influx of refugee students.” Most of them were displaced by the Syrian civil war that began in 2011. In September 2015, the body of 3-year-old Alan Kurdi washed up on a Grecian shore, prompting Canada to open its doors more widely to Syrian asylum-seekers like Ahmed’s family. According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), 64,765 Syrian refugees arrived between November 2015 and May 2019.

Fatehali’s kindergarten classroom would be Ahmed’s first formal learning environment, so she expected some academic deficits. What she wasn’t prepared for were “the social and emotional challenges we would both have to overcome.” For instance, she’d assumed he’d experience separation anxiety, but didn’t realize school bells and airplanes overhead would scare him.

To ease Ahmed’s transition, his 17-year-old brother Hamza — whose lack of formal schooling kept him from entering Canadian high school — came too. While Ahmed learned his alphabet, so did Hamza. The older boy also learned simple conversational English. On the last day, the kindergarten students received report cards. Hamza asked Fatehali where his was.

Fatehali didn’t realize school bells and airplanes overhead would scare her new student.

“I, of course, did not have one for him. But instead told him all that he had learned and accomplished,” says Fatehali. “I could see he was proud of himself. Through school, Hamza learned that he was accepted and valued in his new country.” This moment made Fatehali realize that helping refugee students feel they belong could be a stepping stone to success in their new country. She went searching for tools to help teachers do just that.

When Syrian refugees began arriving, IRCC had published a population profile — containing information about Syrian newcomers’ demographics, cultural considerations, and health characteristics — which the BC teachers’ union had given its members. The profile provided a helpful baseline, but Fatehali knew building bridges in the classroom would require stories kids could relate to.

She found herself staring into a void where there should have been children’s literature — particularly picture books — about refugee kids settling into new environments. “There wasn’t any literature out there that didn’t just talk about a refugee crisis,” says Fatehali, who is also a PhD candidate in early childhood education at Concordia University Chicago, and founded Thrive Kids!, a learning-coaching company.

She decided to write a book herself in which new students could see themselves, and other students could glimpse a newcomer’s viewpoint. She drew on her own family’s experience leaving Kenya after neighbouring Uganda expelled residents of Asian descent in 1972, triggering fears of similar expulsions in nearby countries.

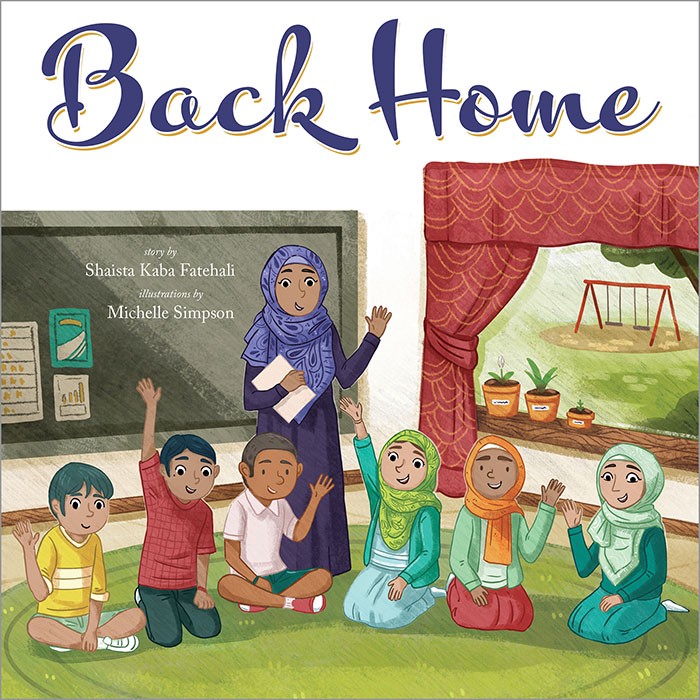

The result is Back Home (2019), the story of 5-year-old Asha on her first day of school in a new country. As a first-time writer with no agent, Fatehali faced repeated rejection in her search for a publisher, some of which she thinks stemmed from the story’s central family being Muslim. In the end, Back Home found a home with Virginia-based Brandylane Publishers.

As Asha enters her classroom, she’s bombarded with the unfamiliar and afraid to leave her father’s side. Throughout the day, Asha’s classmates smile at her and include her in their play, and she notes similarities between the values of patience and generosity in her new classroom, and those in her class back home. She remembers old friends fondly as she connects with classmates. At the end of the day, Asha realizes: “I feel happy. I feel like I am at home.”

One of the greatest challenges at the elementary school level is the lack of teacher training in how to support refugee students.

“It is extremely important, when we deal with kids, that we create a sense of, ‘Home is where we are,’” remarks Neila Miled, a PhD candidate in educational studies at the University of British Columbia who has extensively explored the topic of “home.” Her research includes a project with high school girls from refugee backgrounds who were given cameras to document their experiences and concerns. She’s also worked with a community organization to help resettle Syrian refugees.

A major finding of Miled’s research is that: “No other institution in our society could make you feel [more] at home, or homeless, like schools.” The teacher’s role, then, is crucial. Unfortunately, Miled explains, “one of the greatest challenges at the elementary school level is the lack of teacher training in how to support refugee students.”

Fatehali concurs. She had to change her dissertation topic because she couldn’t find enough teachers to study who had training in working with refugee students. That lack of teacher training coupled with non-existent literature reflecting these students’ experiences makes the need for a book like Back Home even greater.

Refugees come from all over, so Fatehali wanted the book to be relatable to children with a range of experiences. To that end, she created a main character who is Muslim, but doesn’t have a distinct national identity: “If I say this girl is from Syria then it kind of shuts people out.” To nail Asha’s generic Muslim look, Fatehali collaborated with illustrator Michelle Simpson on details like Asha’s dress and hair covering. Though Asha covers her head with a scarf, some of her hair peeks through, which is acceptable for children in many Muslim cultures. Her school clothing could be worn in many parts of the world.

This decision has proven fruitful. Fatehali finds that kids reading her book relate to Asha, regardless of where they were born or whether they’ve experienced trauma. Many children she’s met when reading the book at schools have told her about feeling uncomfortable in new situations or not wanting to leave their parents. Fatehali’s goal was a book children from refugee backgrounds could relate to, but it turns out Asha’s story holds meaning for their classmates, too.

Print Issue: Summer/Fall 2020

Print Title: This Book Builds Bridges