Public Art Mosque Opens Gates to Conversation

It may look like a cage, but a new installation in Vancouver aims to build bridges.

Ajlan Gharem’s public art installation Paradise Has Many Gates will spend two years in Vanier Park as part of the Vancouver Biennale.

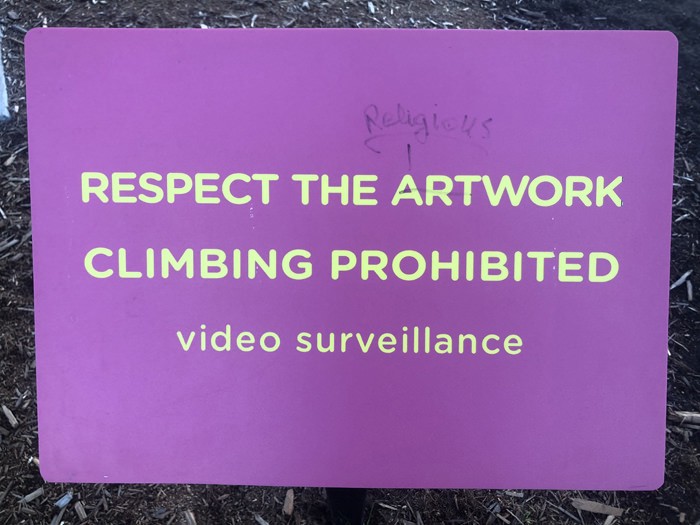

Amid the green hills of Vancouver’s Vanier Park — with False Creek and English Bay in the background — stands an industrial steel structure. The 10 by 6.5 metre building resembles a cage, or the skeleton of a little mosque. Through its chain-link walls you can see prayer rugs, and a chandelier hanging down from the central dome. A nearby sign reads “RESPECT THE ARTWORK. CLIMBING PROHIBITED. Video surveillance.” Someone has scratched out the word “ART” with a black marker, and written “Religious” in its place.

Saudi multidisciplinary artist Ajlan Gharem’s “Paradise Has Many Gates” was installed in the park in June as part of the Vancouver Biennale’s current exhibition, re-IMAGE-n, which aims to raise awareness of critical global issues. It’s not the first time the Biennale has included a Muslim artist’s work, but, according to curator Zarina Laalo, it’s “the first time a work has specifically addressed Muslim topics using Muslim iconography and symbols.”

“The piece,” said Laalo, “which represents the epitome of gathering space and community, allows local groups of all faiths and beliefs to come forth and celebrate this idea of inclusivity, acceptance, and freedom in creative and engaging ways. It is our wish — in addition to the artist’s — for this space to serve as a conduit for a healthy dialogue between multiple groups and generations.”

The altered sign at the Paradise Has Many Gates installation

Gharem first created the installation in 2016, and has exhibited it around the world, including in his home country of Saudi Arabia; Houston, TX; and London, UK. When the artist was in Vancouver in June, he participated in an event hosted by Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Comparative Muslim Studies (CCMS). At Being a Muslim Artist, Gharem screened a short film about the installation, consisting of timelapse footage of the mosque as it stood in the Arabian desert. It shows people of different ages and ethnic/social backgrounds entering the structure and praying.

The meaning and the feeling of the work changes depending on location and context.

“One thing we have discovered was that the meaning and the feeling of the work changes depending on location and context,” Laalo said. “Having it at Vanier Park completely changed the way it was perceived than when it was in [Houston’s] Station Museum or in the desert.”

At one point during the 4-minute film, the subjects look out of the structure with fingers gripping the steel fencing. According to a Biennale press release,

Ajlan’s mosque is built from the same cage-like material that Western countries use to erect fences along their borders, preventing refugees and illegal immigrants from entering. While it can evoke feelings of imprisonment and anxiousness by way of its caged structure, this work has also been often interpreted with a positive sense of openness and transparency; this work functions as a communal centre of prayer, and invites all visitors, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, to question how we designate and behave within sacred spaces, and how their meaning will differ between generations and cultures.

The chain-link mosque at sunset, backed by English Bay and the North Shore Mountains

In conjunction with the installation, the Biennale launched other events, including Weaving Cultural Identities, at which Indigenous and Muslim textile artists were invited to weave prayer rugs to cover the mosque floor. “We are most humbled to have started reaching out and connecting with the Muslim Community, as well as the First Nations community,” said Laalo. “Many local Muslim groups and First Nations groups that we have encountered are already interested in developing intercultural relations, acceptance, and inclusivity, and I think this really comes across in the programming.”

This series — including calligraphy workshops, a multimedia event on “gender and Muslim perspectives,” as well as a mural in the Vancouver Mural Festival sponsored by the CCMS — was created to highlight the cultural and artistic expressions of Vancouver’s Muslim community, and to start a dialogue in which its members can represent their own identity, speak for themselves, and build relationships with other local communities.

Our aim is to create space where local Muslim artists feel included and represented in Canadian society.

“We think that these events will bring change to the way Muslim communities are usually perceived,” said Amal Ghazal, director of the CCMS. “Our aim is to create space where local Muslim artists feel included and represented in Canadian society, and where they can express themselves and their diverse identities and background.”

Whether this piece and accompanying programming succeed in creating change is yet to be seen. Judging by the graffiti on the “Respect the artwork” sign, what’s clear is how necessary that change is.