Artists Are the Architects of Activism We Need

Dreamers and creators can break imaginative barriers and lead us to a better world.

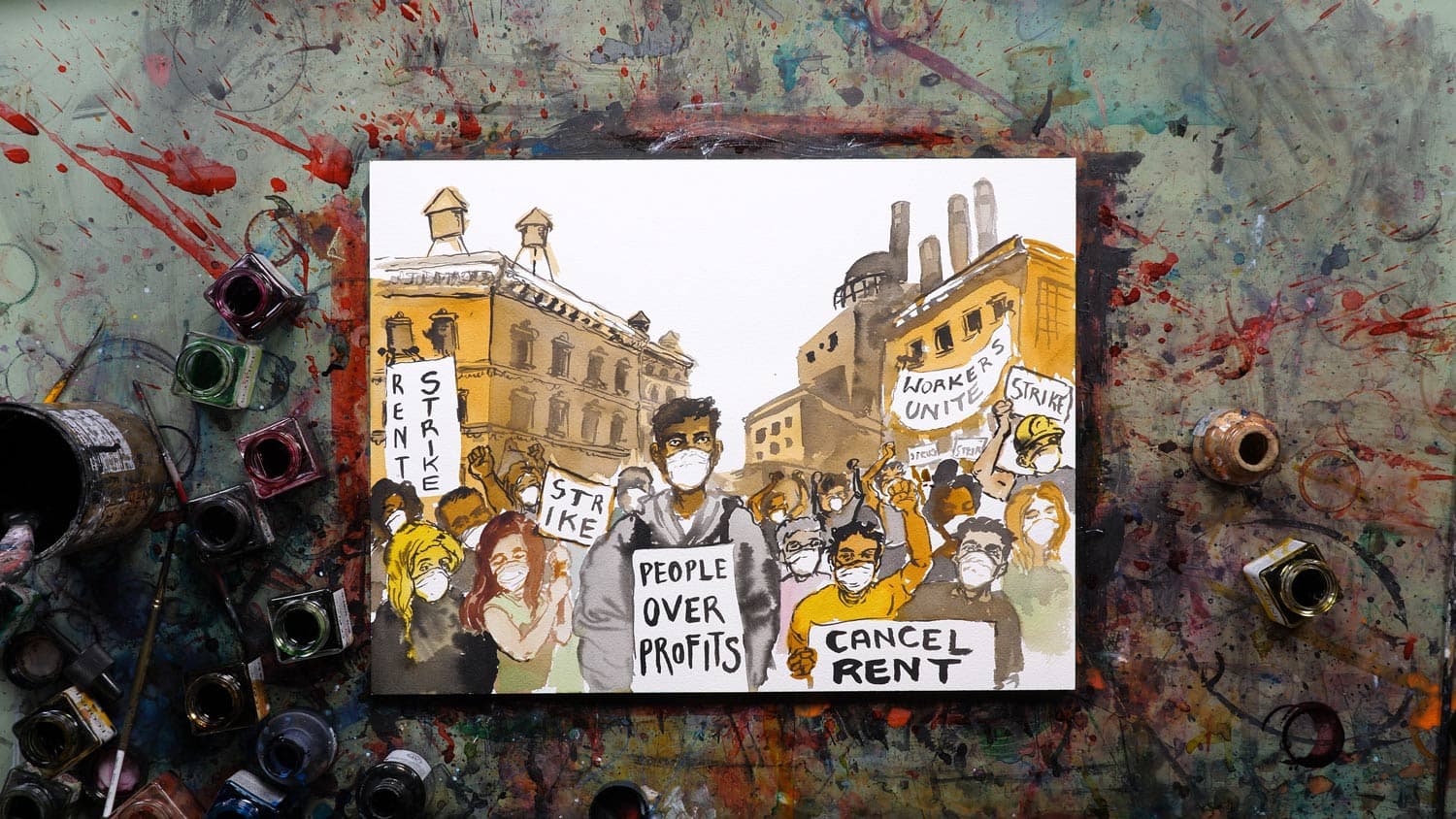

Film still from The Years of Repair by Molly Crabapple

In her book, War Talk, Arundhati Roy wrote: “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way… [On] a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.” Well, from where I stand, we can now hear her roaring. Because of the inequality unmasked by the Covid-19 pandemic, the gap between what we dream is possible and what we expect from our government is shrinking.

What do I hear in this new world’s roar? A national child care program to support parents, especially women, who do the lion’s share of care work. A universal basic income, so that nobody struggles to put food on the table. A transition to clean energy and an economy that works within nature’s limits. To help pay for it, taxes on the wealthiest among us, some of whom have profited from the pandemic while society’s most marginalized suffered. There are no guarantees, but so much of what activists have been asking for to build greener and more equitable societies has begun to win popular support.

Artists and dreamers have the capacity to broaden people’s sense of political possibility.

This other world needs no fanfare of trumpeters; she is heralded with choruses of “No Justice, No Peace.” She needs no conquering army; she is led by legions of youth demanding the climate justice adults have failed to deliver. But the biggest barrier to the arrival of a better future? Too many people still can’t imagine that things could be different. Changing this could change everything.

As governments in Canada, the US, and around the world ponder what it means to “build back better” from Covid-19, artists and dreamers have the capacity to broaden people’s sense of political possibility.

With Greenpeace Canada, I’ve been lucky enough to work on projects harnessing the power of art, including working with Indigenous artists who designed powerful imagery for banners used in an aerial blockade of an oil tanker in Vancouver in 2018. The symbolism of the banners became a gateway for talking about the issues at stake in the fight against tar sands expansion. Such gateways are crucial for understanding, and overcoming, the current crisis of political imagination.

The fossil fuel lobby has spent decades convincing people that climate science is uncertain (it isn’t), and that even if climate change were happening, we couldn’t do anything to stop it (we can). Evidence has been laid out at length by experts like Harvard researchers Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes, who found that oil companies have known for decades their products would lead to climate change, but ran PR campaigns to mislead us about it.

When you feel helpless on climate change, that narrative was likely seeded by the fossil fuel industry.

“When you feel helpless on climate change,” says Grace Nosek, a doctoral student at the University of British Columbia studying how the law can be harnessed to address the doubt seeded by the oil industry. “Think that that narrative was likely seeded by the fossil fuel industry,” she says. “Remember it, and then try to push back against it.”

When you break the power of old narratives, you create space for new ones — and for new real-world possibilities. One game-changer has been the emergence of persuasive protagonists in the climate justice story: from youth climate strikers like Greta Thunberg and Vanessa Nakate, to New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to Black Lives Matter co-founder Opal Tometi.

Ocasio-Cortez and Tometi were recently part of a beautifully rendered video series inking out a vision of a better world. They collaborated with artist Molly Crabapple, journalists at The Intercept, and thought-leaders from The Leap (a climate justice organization co-founded by author Naomi Klein and documentary filmmaker Avi Lewis). The Leap’s stated mission is to “make system change irresistible.”

The 2019 Emmy-nominated short Message from the Future is an animated “look back” at a successfully implemented Green New Deal, told from the perspective of Ocasio-Cortez. The 2020 sequel, The Years of Repair, imagines a post-pandemic world where care, a green transition, decolonization, and reparations are at the centre of the economy. It was co-written by Tometi and Lewis.

“It was a huge breakthrough,” said Lewis of the first film. “It struck a political moment when people just were hungry for it.” Still, skeptics continued to dismiss the Green New Deal as undoable.

“Those big ideas — what is it that prevents us from tasting them in our mouths?” Lewis remembers he and Klein asking themselves. “What is it that prevents us from believing that change on that scale could and should happen?” The answer? “It’s just that block of imagination.”

For Prashant Miranda — a visual artist based in the seaside village of Lund, BC — art is a powerful tool for dismantling this block. “[Art is] a release of ideas, of hope, a language which cannot be communicated,” Miranda told me. “It’s an intangible form that allows you to connect universally. In that regard it really unlocks the unimaginable.”

Message from the Future was meant to do just that. Years of Repair seeks to dig deeper into how a just society can be achieved on a global scale. The films have been viewed millions of times, and are used as public education tools by The Leap’s partner groups, including the Movement for Black Lives, Global Nurses United, NDN Collective, and more.

Lewis, who co-wrote both films, calls them “documentary futurism”: using the language of documentary journalism to describe the world as if looking back from the future. Documentary futurism can unleash our political imagination, he says. “It helps us see how we get to a better place from where we are now.”

Those big ideas — what is it that prevents us from tasting them in our mouths? It’s just that block of imagination.

Miranda sees similar possibilities. Leaving behind the commercial children’s animation industry where he got his start, Miranda now pursues art independently, inspired by how nature connects with culture.

“I’m not a frontline activist at all,” he insists, though his art is infused with activism, from documenting the story of a felled oak tree in Toronto, to creating nature-based designs for traditional quilts made from upcycled saris as part of a livelihood-generation project for women in Varanasi. Recently, when political violence erupted in his native India, Miranda poured his feelings into his sketchbook. “I was feeling terrible. I thought: I’m not in India, what am I going to do?”

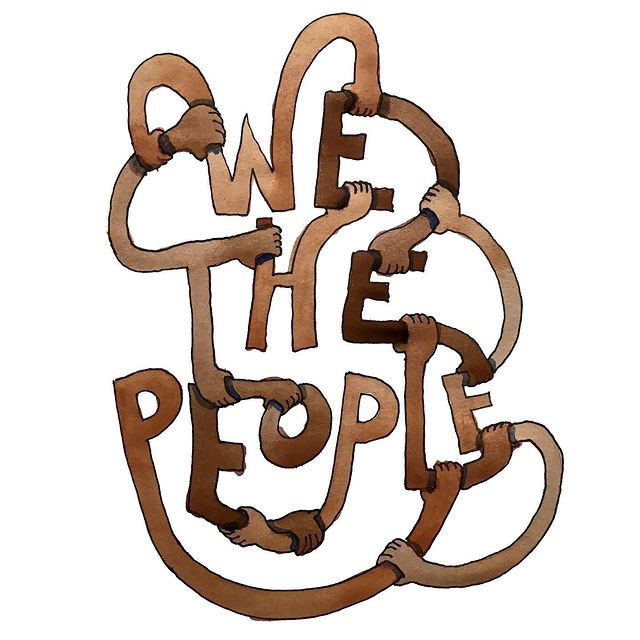

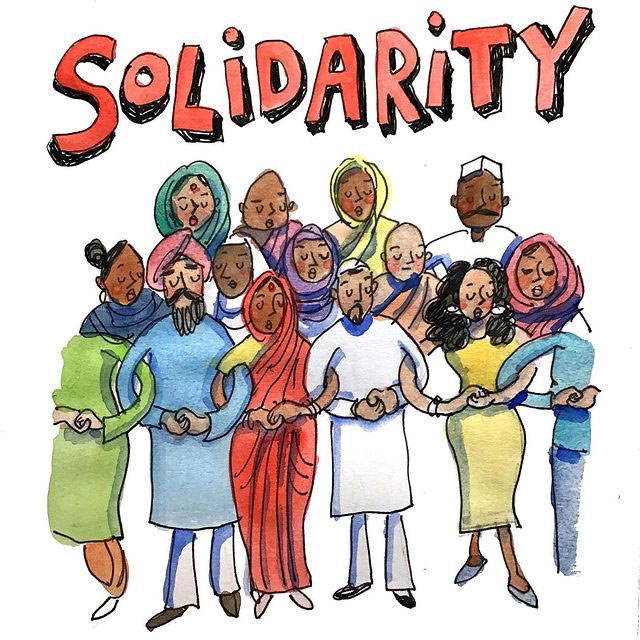

Prashant Miranda’s images of solidarity were shared widely as part of a protest movement in India in 2019.

That’s when images of solidarity came to him. “Everyone, coming from all different kinds of backgrounds, was hand-in-hand,” he says of the water-colours he created and posted on Instagram. “That next day, I saw that image being used in frontline protests [in India]. Right from my headquarters here in Lund, it was actually reaching the frontlines. Then I saw it being used with [a news] headline.” Seeing his art shared widely on Facebook and Instagram, Miranda reflected, “It was really powerful that I needn’t be helpless.”

Literature can likewise turn helplessness to hopefulness. I spoke to Marcelle Kosman, co-host of the podcast Witch, Please. On the show, Kosman and her co-host Hannah McGregor explain complex social issues, like white nationalism and classism, through the lens of the Harry Potter novel series. For Kosman, sharing tools people can use to understand, analyze, and describe cultural narratives and systems is important. Fiction, she says, is a “low-stakes alternative kind of reality” that can nudge people to question the world they live in by imagining it differently.

“One of the things that has been really motivating for both me and Hannah has been people writing in and people telling us that the podcast has allowed them to see things differently,” she says. “The other thing that’s been really cool has been hearing from people who have felt … like they had the language to challenge either friends or family members who had hateful opinions.”

Reconceiving struggles as movements, rather than as heroic individual projects, is the only way to overturn the order that threatens our species.

Something Kosman would like to see more of is fiction that engages with the environmental anxiety experienced by millennials and Gen Z. Author Cory Doctorow is doing just that, currently at work on a novel set in a post-Green New Deal future. He told me via email that the most urgent narrative to overcome is the neoliberal story that individual consumer action is the only solution to the climate crisis. “Reconceiving struggles as movements, rather than as heroic individual projects, is the only way that we will be able to successfully overturn the order that threatens to render our species extinct,” he concluded.

From sketchbooks to social media to novels, activist art can transform a passive hope for Roy’s other world into a collective movement that will paint, write, and march her into being. In Avi Lewis’ words, “to actually collectively create the world we’re fighting for is much less a political muscle and much more an artistic one.”

Print Issue: Winter 2021