Are Best-Before Dates the Worst?

Meant to indicate freshness, these labels can lead to wasted food and money.

Food touches a nerve. How we see it depends on a host of factors like culture, social class, and economics. Food is hardly ever just food. It’s loaded with meaning and emotion. Generational differences—even notions of morality—colour how we perceive it. Rising food prices, our truly staggering level of food waste, and its equally staggering environmental footprint mean we need to recalibrate our approach.

My capital-B Boomer husband calls waste a capital-S sin. Trespassing onto my turf seeking evidence of my wastefulness, he’ll grab an open tub of yogurt coated with gray-green fluff, or maniacally wave around a half-empty can of tomato paste.

Today it’s me, vintage Gen-Xer, foraging for culinary treasures for an upcoming dinner. I discover a 2-kg package of frozen halal chicken wings marked with a best-before date (BBD) of July 23, 2023. Preening like rubies in my crisper drawer are a dozen tomatoes grown in Mexico but packaged four weeks ago nearly 3,800 km away in Kingsville, ON.

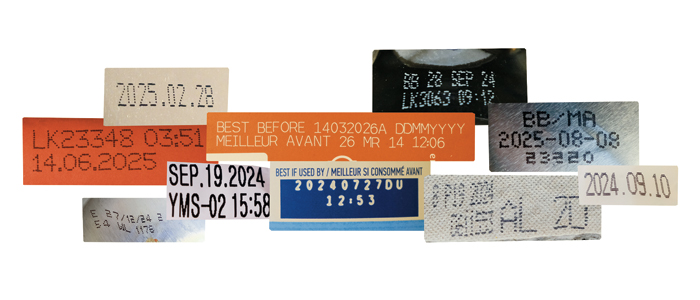

Best-before dates are everywhere and they’re baffling. Divorced from the messy reality of how field crops and mooing farm animals morph into tidy units of retail nutrition, shoppers frequently confuse “best before” with “bad after.” But BBDs merely indicate peak freshness of say, a carton of eggs, not that swallowing those eggs past the stroke of midnight confers sickness. BBDs denote quality, not safety.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency mandates BBDs on products with a shelf life of 90 days or less. But industry players stamp BBDs or packaged-on dates on a host of staples, including dried pasta. Expiration dates apply to only five products: infant formula, liquid diets for tube-feeding, supplements, meal replacements and medically prescribed very low energy diets. Their nutritional value dwindles past the expiry date.

Lori Nikkel, a self-described former low-income single mother who is now CEO of Second Harvest—Canada’s largest food rescue non-profit—says we simply don’t value food. She laments, “Food has grown too far away from us. We don’t care about it.” Instead of a precious resource that keeps us alive, we’ve degraded food to an aesthetically pleasing commodity.

Consider planned obsolescence. This business strategy—whereby products engineered to break down within fixed terms force consumers to upgrade to new models—was once reserved for bikes, cars, and electronics. Now we apply it to the food we eat. Agri-industry regulates this practice via often arbitrary BBDs, which means that as consumers we’ve been conditioned to toss out perfectly edible food.

Agriculture is big business. Each player needs to turn a profit. Nikkel says our supply chain produces too much food in a year, enough excess to feed every Canadian for five months. Manufacturers downstream ship packaged food to retailers who slap on BBDs. Retailers often discount prices close to the BBD; they don’t want stale products taking up shelf space. They need to move that inventory down the food chain.

Enter Joe Shopper. Joe wants to eat fresh affordable food without getting sick. He stores his perishables, say a bag of greens, in a fridge optimally set to 4°C. A few days later, Joe decides to whip up a salad. The leaves look crisp, not slimy, but the bag is past its BBD. Joe’s not taking chances; he chucks it out. Next week, he buys another bag. Joe spends more grocery dollars, retailers move in fresh stock, manufacturers sell more product, and farmers grow more lettuce.

As consumers, we’ve been conditioned to toss out perfectly edible food.

In a land of plenty, where everyone can afford to eat, this is a nearly win-win scenario. But 6.9 million Canadians are food-insecure, which is a fancy way of admitting that a sizable chunk of our population goes hungry. In 2022, the Consumer Price Index measured retail food price increases of 11.4%, exceeding the average 6.9% inflation rate.

This February, Second Harvest published new research showing that food charities anticipate an 18% rise in demand for food aid in 2024. In Toronto alone, demand is projected to increase by a whopping 30%. That’s 1 million additional Canadians—many of whom are housed and employed—who’ll seek food charity this year.

According to Second Harvest, nearly 60% of food produced in Canada gets wasted annually. Of those 35.5 million metric tonnes, 11.2 million are good to eat. The edible waste gets dumped in thousands of landfills. As that mountain of food rots, it produces methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. According to the UN Environment Programme, methane’s unique chemical structure retains more atmospheric heat than carbon dioxide and is over 80 times more potent.

Against this backdrop, a June 2023 report by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food recommended the federal government investigate how eliminating BBDs would impact Canadians. Last October, a private member’s bill that aims to reduce food waste and re-visit problematic food labeling passed first reading in the House.

Sylvain Charlebois, director of Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab, says that BBDs originally helped retailers rotate stock. It’s essentially inventory management. He admits that we’ve “gone overboard” when even salt and honey are dated. Although he believes BBDs are overused, he thinks scrapping them is unwise. Shifting the balance of power could disincentivize retailers to offer discounts on stale stock, hurting consumers.

“People grab milk at the end of the shelf, not the one next to them. They’re also buying freshness and time. Without dates, you can’t empower consumers to pick and choose what’s fresh.” Instead of eliminating BBDs, he advises educating consumers that “best before” doesn’t mean “bad after.”

He makes a case for the industry. “It’s not criminal [for companies] to make money.” If a disgruntled customer eats non-perishable food months or even years later and complains on social media that it tastes bad, that complaint damages the brand. “There are tremendous risks for the industry to operate without dates.”

Nearly 60% of food produced in Canada is wasted every year.

He cites a 2022 report his lab collaborated on with pollster Angus Reid, which found only 27% of Canadians wanted to eliminate BBDs. The report showed that the category of food matters, too. Nearly three quarters of those polled checked BBDs on dairy products; only 32% checked dates on non-perishables. And 65% threw out unopened food past its BBD. Charlebois concludes Canadians see value in those dates because they prioritize food safety over the environment.

Tesco, Britain’s largest grocer, scrapped BBDs on more than 180 types of fresh produce back in 2018. Charlebois doubts such a move would be popular here.

Keith Warriner, former chef, now University of Guelph microbiologist, explained to me how grocers determine BBDs. The manufacturer asks the retailer, “what shelf life do we expect for this product?” Manufacturers then formulate products to delay spoilage by adjusting the pH or packing them in oxygen-poor conditions. That’s when the clock starts ticking. Take deli meat. After being preserved with sodium nitrate, its shelf life extends to 60-70 days, long enough to travel to the distributor—Canada’s a big place—then to the grocer who hopes it sells soon, because no one wants to sell spoiled meat.

Companies set up in-house studies where they set the product in the refrigerator and wait, using sensory analysis—looking, sniffing, and tasting—to gauge when it’s spoiled. Sometimes, for extra wiggle room, they dial up the temperature to 10°C, when food spoils faster. The BBD could be five, 15, or 30 days onward, depending on whether we’re discussing soft cheeses or yogurt.

A more rigorous but less common approach identifies the growth of specific spoilage organisms. For instance, yogurt supports the growth of fungus which appears as mold. Mold looks nasty and makes yogurt taste funky, but it isn’t necessarily harmful.

“Best before” doesn’t necessarily mean “bad after.”

Meanwhile deli meat, seafood, and lettuce support Listeria, a hardy bacteria that’s undetectable by sensory analysis and can cause sepsis or meningitis—especially in newborns, according to the Mayo Clinic—and fetal demise in pregnant women. Lab technicians inoculate a product with a particular bug, hold it at the standard 4°C (or higher for extra caution) then note when microbial growth exceeds a certain count. The safety cut-off for Listeria is 100 colony-forming units (CFU)/gram, far below its infectious dose, which for healthy people ranges from 10-100 million CFU/gram, depending on the bacterial strain.

The trouble with eliminating BBDs, microbiologist Warriner says, is having to trust retailers. Only they know how long that product’s languished on their shelf. By the time deli meat reaches day 60, will retailers discount it, divert it to food banks, or trash it? He suggests developing a hybrid system, so consumers who want BBDs can download an app to scan the product, while others simply bypass this step.

Back to our family dinner. I thawed last summer’s frozen wings, seasoned them well and baked them in a hot oven to smash reviews. But I didn’t tell my son-in-law the BBD was eight months ago.

Print Issue: Spring/Summer 2024

Print Title: The Dating Game