Bark Beetles Weren’t a Menace Until Humans Turned Them into One

Thanks to climate change and short-sighted forestry practices, bark beetles harm trees, wildlife, and industry.

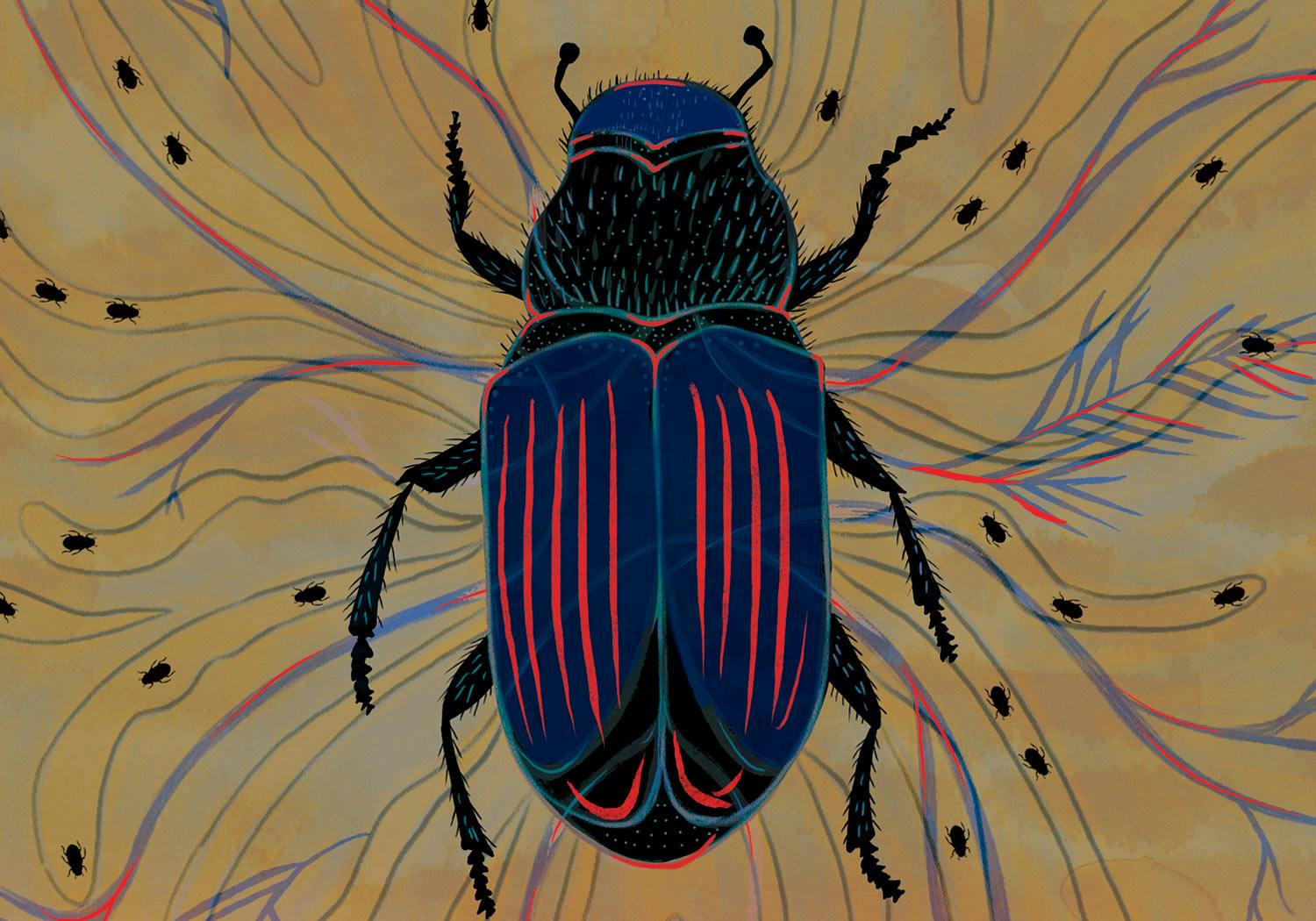

Bark beetle females bore through their host trees’ inner bark, creating “galleries” in which to lay their eggs. Larvae then continue the tunnelling process after they hatch.

The bark beetle is a tiny creature with a massive impact. Out of more than 6,000 species, the best-known is probably the mountain pine beetle, which is only as big as a pencil eraser. And yet, thanks to these itty-bitty bugs, an average of 100,000 trees falls every day in the US, according to its national forest service.

In recent years, beetle infestations of living trees — most notably an ongoing outbreak of mountain pine beetle that started in British Columbia in the 1990s — have wreaked havoc on forests in western North America. And the damage they cause trees creates problems for industry, the climate, and much larger forest-dwellers. But it didn’t used to be this way.

Beetle infestations have wreaked havoc on forests in western North America. But it didn’t used to be this way.

Each beetle species is tree-specific, with most species preferring to dine on particular types of dead tree. Some species, like the mountain pine beetle, gravitate toward ailing live trees: the old, the weak, the dying. Bark beetles can carry with them multiple symbiotic fungi, some of which break down wood. The nutrients in decomposing wood are more bioavailable — easier for both larvae and adults of most species to eat — and also a better substrate for fungus, which provides an additional food source for adult beetles. This process returns the tree’s nitrogen and carbon to the soil, fueling new growth. It’s a vital step in the forest life cycle, when that cycle is in balance.

“A third of forest species live in and on dead trees,” writes Norwegian biology professor Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson in her 2018 book Buzz, Sting, Bite: Why We Need Insects. “Bark beetle attacks have always occurred as part of a natural disturbance regime in the boreal forest,” she told me in an interview. “Usually, these attacks were regenerative events, creating sun-exposed gaps in the forest where new trees could grow.”

Vast areas of BC pine forest have turned red from mountain pine beetle infestations since an outbreak started in the 1990s.

Unfortunately, our climate is changing, and with it this equilibrium. “We have a warmer and drier climate,” Sverdrup-Thygeson said. “This is disturbing the dynamics that used to limit the extent and severity of these outbreaks.”

The result? Trees are more stressed, making them easier targets. Fewer insects die from cold during the winter, leaving larger spring populations. Warmer weather means beetles reproduce in greater numbers and offspring reach maturity faster, creating larger swarms of adult beetles with greater nutritional demands, capable of surviving at higher altitudes. As populations grow, and the selection of ailing trees dwindles, tree-killing beetles attack the healthy as well. The beetles’ specificity makes them especially dangerous to monoculture forests planted with trees of a single species, all at the same growth stage.

Bryan Lamont, field researcher at the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, studies mountain pine beetles in the Rocky Mountains. The outbreak cycle, Lamont told me in an interview, begins when a forest disturbance of some kind creates a boom in beetle populations. Drought and disease can weaken trees, as do storms, which may also spread beetles outside their normal range on the wind.

The outbreak cycle functions like this:

- Beetles lay eggs in vulnerable trees, most often in late summer, within “galleries” they’ve bored in the inner layer of bark. The eggs hatch and grow into larvae, which continue tunneling through the tree. The larvae pupate, then emerge as adults who go on to lay more eggs, in the same tree or another nearby. Cooler temperatures slow this process, while warmer temperatures speed it up, with the cycle taking as little as six months or as long as two years. Beetles spend their entire lives inside the tree, except for the brief few minutes when they fly off in search of a host where they can lay new eggs.

- Infested living trees inevitably die, their circulatory and immune systems compromised by the consumption of their inner bark and the spread of different symbiotic fungi, which protect beetles from the trees’ natural defenses. It can take weeks or months for infested trees to show signs of sickness like reddening needles, and even longer for them to succumb.

- When all the occupied trees in an area have been killed, losing their foliage, the forest is said to have entered “the grey stage.” Beetle populations stabilize, or the bugs move on. The dead trees can remain standing for as many as 15 years, depending on factors including species and soil conditions.

- The grey stage ends when all the dead trees are downed.

According to Jeanne Robert — an entomologist for BC’s forestry ministry in the province’s northeast — mountain pine beetle populations are starting to stabilize in her area, but a spruce beetle outbreak is ongoing. The spruce beetle population was just entering a phase of rapid increase in 2016 when Robert started working for the ministry.

The shift, she said in an interview, traces back to windstorms in 2010. Beetles in these forests found homes for their eggs in downed white spruce. By 2014, the exponential growth of the beetle population resulted in healthy trees being infested, and in 2015 an outbreak was declared. By 2017, over 500,000 hectares were affected. Robert hopes this number represents the peak of the outbreak, but it’s only a matter of time before the next.

Biologist Sverdrup-Thygeson wants the world to fall in love with bugs, but she’s the first to admit bark beetles might not be the easiest place to start. She knows how disastrous these outbreaks have been. “In the long-time perspective, nature will handle it one way or another. But it can have devastating consequences as seen from our human time perspective. It creates a source of more carbon emissions. New forest will not necessarily regenerate in all areas. It will have far-reaching consequences for other species.”

For instance, Lamont’s most recent study in Wyoming focused on how this deadfall affects herds of forest-dwelling elk, the primary large mammal in beetle-killed forests of the Rockies. After logging or fire, areas newly opened to the sun naturally attract grazing animals with an increase in undergrowth. Lamont found, however, that this wasn’t the case for forests disturbed by beetle-infested deadfall. Deadfall zones encourage forest-floor growth, but also create a dangerous obstacle course for elk. They must not only endure the heat of the sun, but navigate fallen logs without injury.

We need to take the blame off the insects and put it where it belongs, on human activity.

“Elk try to minimize unnecessary movements as to not burn hard-earned fat reserves that they need to survive through the winter,” Lamont said. “If there are dramatic structural changes (i.e. lots of downed trees) during the treefall phase, elk may avoid these areas unless it is absolutely necessary.” Outbreaks, then, are likely pushing elk out of their usual habitats, potentially increasing their interactions with human dangers like hunters and drivers, and making it more difficult for wildlife management to track herds.

Forest entomologist Diana Six has dedicated the past 25 years to understanding bark beetles, and has seen the mountain pine beetle outbreak’s effects up close in Montana. “So many people look at the mountain pine beetle like the antagonist, the bad guy,” she says in her short film, Life of Pine. “But really it’s just an organism doing what it does. We really need to take the blame off the insects and put it where it really belongs, on human activity.”

Having turned bark beetles into “the bad guy,” what can we do? Their role returning nutrients to the soil is too critical for us to consider eliminating them. But there are ways we can both prevent the spread of outbreaks, and help devastated forests recover.

Jason Forsyth is the CEO of Inlailawatash Limited Partnership, a company owned by the Tsleil-Waututh, an Indigenous nation whose traditional territory includes Vancouver, BC. Inlailawatash manages the coastal old- and second-growth forests in the Indian River watershed, about 30 km northeast of Vancouver. They’ve only experienced minor infestations of Douglas-fir beetle, and Forsyth intends to keep it that way. According to Forsyth, the Tsleil-Waututh nation’s approach to forestry is based on “holistic, ecosystem-based forestry, where you’re really doing everything you can to keep these systems functioning at a healthy level.” This involves protecting large areas from any human disturbances.

These values seem to have support from Canadians, who overwhelmingly agree that the country, and the world, should drastically increase the number and size of protected wilderness areas. This shift in priorities is also supported by science. According to Buzz, Bite, Sting: “woodland consisting of natural forest contains more predatory insects and parasites that keep spruce bark beetles and other pests in check.” Old-growth forests also have healthier soil and store massive amounts of carbon.

Maintaining more natural forests is a prospect that many working in forestry may, unfortunately, see as a threat. “I think one of our problems as humans,” Inlailawatash CEO Forsyth told me in an interview, “is if it is competing with something we want, which is usually timber, we see it as a pest.” It’s easy to see bark beetles as the enemy when our jobs depend on them starving, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

Forsyth admits there are sacrifices involved in shifting our perspective on forests. “If we protect the value of this area, that’s going to mean less logging, less jobs, less revenue in that short-term period, which is very real for people that are potentially going to lose a job.” He thinks, however, that we need to take a longer-term view.

Where industry tends to move in four- or five-year cycles, trees count their lives in hundreds or thousands of years. “If you take a longer-term view — of a cutting cycle of even 60, 80, 100 years — I think that conversation changes a lot, because the timber industry has a chance to look at what are all the other benefits that come from protection. […] A health-based approach at the beginning, in theory, could actually increase your timber value over time,” he suggested, perhaps offering more sustainable value and employment.

But according to Robert’s description, the BC forestry ministry is taking a more conventional approach. The ministry’s response consists of government-industry working groups prioritizing areas of the forest for “pest-reduction harvesting,” which involves removing beetle-infested live trees, and can result in clearcutting of particularly heavy-hit areas. Other solutions include controlled burning, pesticides, even synthetic beetle pheromones to control their spread.

Professor Six’s work raises concerns about the impact of conventional methods. Six Lab has studied the rare trees in otherwise devastated areas that were able to withstand beetle infestation. Their team identified specific genetic differences between these trees and the vulnerable, dead ones. Six’s research poses the question: What if while attempting to protect vulnerable forests in the short-term, we’re actually destroying the trees that could save them in the long-term?

What if while attempting to protect vulnerable forests in the short-term, we’re actually destroying the trees that could save them in the long-term?

A Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks study released in August tracked an elk herd in the Elkhorn Mountains for four years, and suggests a long-term view is what the elk need as well. Despite not grazing among beetle-felled trees, elk tended to use the areas for protection from hunters. In other words, a long-range study showed the beetle deadfall wasn’t only bad news for the elk.

Of course, elk aren’t the only species feeling pressure from beetle outbreaks. In a blog post for Yellowstone Park, University of Colorado biologist Professor Diana Tomback explained her concern for the whitebark pine and species that depend on it, particularly grizzly and black bears. Threatened not just by beetles, but by the white pine blister rust fungus, the tree is at risk of extinction, according to Tomback. “I am very worried, but I can’t get depressed and give up,” she told park staff.

Inlailawatash’s Forsyth is also not giving up. “I truly believe that responsible renewable resource management is possible,” he said. “There is an ability that Indigenous people have shown to manage fish, and animals, and other natural resources in perpetuity,” by incorporating “management approaches that have been around for thousands of years, that are being refined with new tools and technology.”

Taking responsibility for our changing environment and our role in it, he said, we need to look beyond industrial extraction and capitalist cycles that peak and crash like beetle populations. This kind of thinking, Forsyth said, is “the future for our planet.”

Correction: This article originally included the claim that all bark beetles prefer to eat and reproduce in dead trees. Some species, like the mountain pine beetle, actually prefer live hosts. The article has been updated to correct this misunderstanding throughout.

Print Issue: Winter/Spring 2020

Print Title: If You Can't Beat'em