Comics Make Xwémalhkwu Teachings Accessible

A new graphic narrative shares elders’ stories with younger generations.

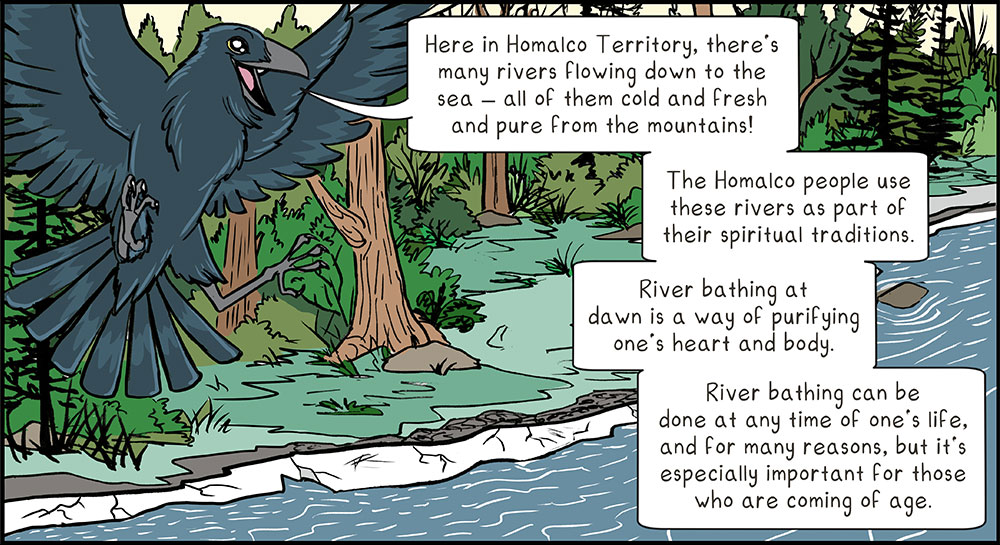

One of Alina Pete’s comic panels for the new book Xwémalhkwu Hero Stories

“It was snowing. [My elder] sent us up to the river to have a bath… His reasoning behind that was, in order for us to become a good man when we grow up, we had to go bathe in the river,” elder Everson Waters explains in a recording describing the coming-of-age rituals of the Xwémalhkwu (Homalco) people. “He said going to the river will help you make those good decisions in your life.”

Waters’ account is included in an episode of Remember—Recordings of Elders Explored, a podcast put out by 100.7 The Raven, the nation’s radio station. His story, along with others from the same batch of recordings, is now being reinterpreted as a graphic narrative titled Xwémalhkwu Hero Stories, set to be released on November 22.

The Homalco First Nation recorded Waters and other elders in the 1990s and early 2000s. They discussed history, tradition, and daily life in their territory, which encompasses the Homathko Icefield and all of Bute Inlet (some 200 km northwest of Vancouver) on the BC mainland and the 100-odd km stretch of Vancouver Island coast between Sayward and Comox.

The recordings were a “treasure that they didn’t know what to do with,” says podcast host Tchadas Leo, a member of both Homalco First Nation and the Stillaguamish Tribe in Washington State. Education Without Borders (EwB)—a Vancouver-based charity that funds educational activities for marginalized communities in both South Africa and Canada—initially approached The Raven about supporting the station’s language and culture programming. The station manager pitched the idea of a series featuring the recordings. He recommended Leo to host based on his past broadcasting experience, and a podcast featuring 11 of the elders was launched to mark 2022’s National Day of Truth and Reconciliation.

In conjunction with the podcast, the comic project aims to help preserve the Xwémalhkwu language—ayʔaǰuθɛm (Ayajuthem)—and, according to Leo, “help Indigenous youth reconnect to their culture even more.” Co-sponsored by EwB, the UBC Comic Studies Cluster (a research group that studies comic art and supports local comic artists), and other UBC departments, the book includes a glossary of translated ayʔaǰuθɛm terms paired with illustrations referencing where they were mentioned in each story. At first, 100 copies of the book will be given to the Nation. Distribution to the wider public is being figured out and will be announced at a later date.

The recordings of elders were a treasure that Homalco First Nation didn’t know what to do with.

Leo selected three BC-based Indigenous artists to write and illustrate: Valen Onstine, who is Nehiyaw (Cree) and Dane-zaa; Gord Hill, who is Kwakwaka’wakw; and Alina Pete, who is Nehiyaw from Little Pine First Nation in Saskatchewan.

In November 2023, a group including Leo, the artists, Homalco First Nation Chief Darren Blaney, the UBC Comics Studies Cluster’s Biz Nijdam, and EwB co-founders Cecil and Ruth Hershler took a trip up to Bute Inlet to kick off the project and build relationships with each other and Xwémalhkwu elders. The visitors toured historic village sites like Muushkin (Old Church House) and New Church House, went whale-watching, and visited Xwémalhkwu hunting camps.

Artist Alina Pete spoke with me over Zoom.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Bring me back to the beginning of the project. How did it start for you?

We spoke to Tchadas online, and he filled us in on what he was wanting to do. He sent us a bunch of recordings beforehand, and I was assigned river bathing and coming-of-age ceremonies, specifically. I listened to that and compared it to some of my own reserve’s coming-of-age ceremonies, which are very different.

From the beginning, we knew that we were going to listen to the recordings and then have this amazing trip out to the traditional territories to meet with some of the elders. Part of working with First Nations communities is developing a relationship with the people that you work with. Biz was really big on trying to set up relationships that go forward and are reciprocal, so we’re each receiving something from this and it’s not just monetary.

Once we got out there, we had a big meal with the elders, one of whom was Tchadas’ father! We got to hear some stories about Tchadas as a kid. We teased each other…it was really fun.

One of the elders was saying that once colonization happened, the government was like, “You used to range in this territory seasonally. We can’t let you do that anymore, so we’re going to round you up and put you over here.”

The elders at that time said “That’s a bad island to set us up on, because the winter storms there are really bad.” They lived there for a few years, and then Old Church House was destroyed in a winter storm.

They were moved to New Church House, which is what’s marked on most maps as Church House. No one lives there today, but most of the buildings are still standing. We went out to Old Church House and New Church House, and the elders were telling us about the fishing areas. They pointed out oyster beds they used to maintain.

What were you curious to ask the elders about?

One of the things that struck me was that, though the cultural differences are really big, talking with the elders felt like talking with my own elders. Often when you ask a specific question, they won’t answer it completely, or they’ll answer it in an oblique way. It’s because part of Native teaching is that people are supposed to figure things out for themselves.

I knew the responsibility that had been put in my lap to tell these stories correctly, even though I’m not from that community. I really wanted to represent them accurately and faithfully, while being aware of the fact that, especially for coming-of-age ceremonies, there’s ceremonial aspects that you don’t talk about outside the community.

So it was like, what can I tell about these stories? We went back and forth on the script. It’s not censorship, but it is protecting intimate knowledge.

The purification ceremonies in our culture would be like one or two ceremonies and the teachings that had led up to it, whereas here it was a year of bathing in the river at all seasons. It has multiple connotations. There’s the physical cleansing, but there’s also the toughening up. You need some physical and mental fortitude to force yourself to go into the waters. The young boy [in my section of the book] doesn’t want to go into the river.

How would you describe your illustration style?

My art style is very cartoony and really appeals to younger kids. I was aware that though [the book] was geared more toward teenagers, it was also relevant to younger kids [who] would be wondering about what would happen when they come of age. I leaned into the kid-friendliness of my art.

We wanted a raven character who was the throughline, that was telling all the different stories about the community. I had a trickster raven appear in the story to talk to this boy, and [the raven] convinces the boy that he should probably just wet his head! I had a cheeky cartoon raven inject a little comedy into an otherwise fairly serious story about a boy coming to terms with what’s required of him to become a man.

Valen has a gorgeous style—it’s more suited to a serious, almost documentary, style of comic. And Gord’s got this amazing style that blends traditional formline art with comic art. I think Tchadas did a really good job pairing us up with our subject matter to take advantage of the strengths of our art.

What does it mean for you to be selected to work on this project?

This was life-changing for me. I’ve been working as a freelance artist [for over ten years] and I’m used to jumping in on a project, learning what I need to get it out the door, making the comic, running it by editors, and then I walk away. And I don’t think about it again.

I knew going in that it was going to be more relational, because they were asking such an intimate thing of me. I approached it in a really different way. I smudged. I went into it with a really true mind of what I wanted to accomplish, knowing that getting to know them as people was going to be really important.

Gift-giving is part of this relational way of working in comics, and I want to carry it forward.

Now, they’re organizing a follow-up as the book is going out. We’re going to do a launch party that all of us are going to travel to. We’re going to have gone on this amazing journey together.

I intend to take some of my originals, frame them up, and give them as gifts back to the elders as a full-circle for my story [of] working with them: “Hey, you entrusted me with your stories, and I hope I told them right. Here is how I want to thank you, by gifting you with the art I made to honour what you have given me.”

That fits with the teachings from my people, but also from out here. The potlatches are famous as a way to show what the artisans of your community can contribute, but also that you have wealth and you’re willing to give it away to other people for their gain and benefit. That gift-giving is part of this relational way of working in comics, and I want to carry it forward into working with Native communities in the future.

What do you want young readers to take from reading the book?

I hope that young kids want to engage their elders and even just their parents. My story was only about a young boy, so girls can ask their female relatives and be like, “What was our coming-of-age [ceremony]?” I also hope that it inspires other kids to tell their stories through comics. They’re just so accessible—they’re so engaging. It’s one thing to pick up a historical book and have to dig through that. It’s another to read a comic.