Food Fight: A Q&A with Eleanor Boyle

Vancouver writer digs into Britain’s transformative WWII food policies to find guidance for our own war on climate change.

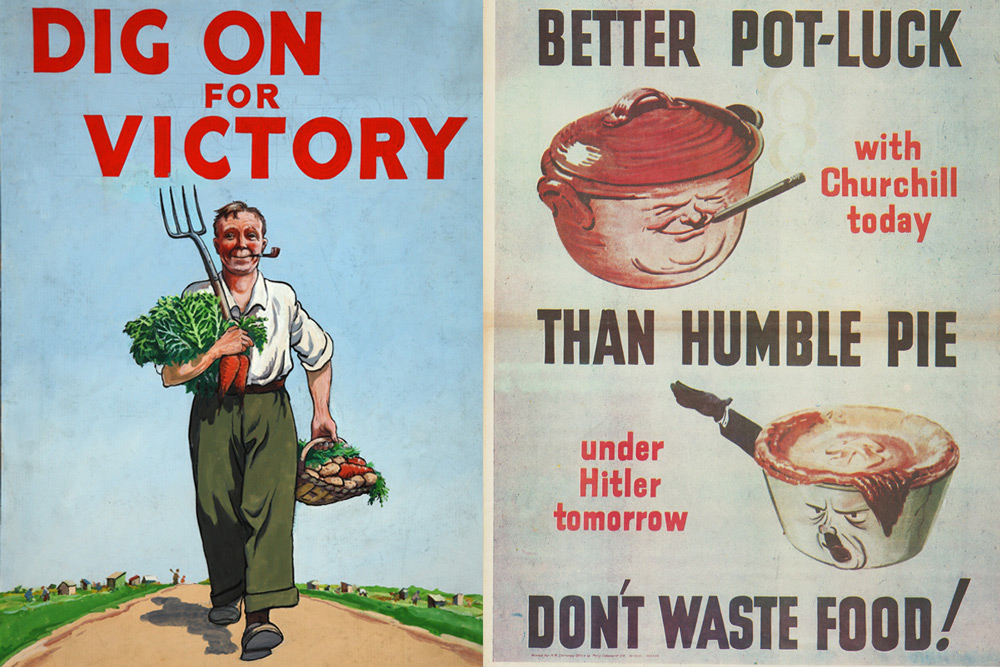

Illustration—A white man with brown hair, holding greens and a pitchfork in his right hand, with a cigar in his mouth.The words “Dig on for victory” are printed in red across the blue sky.

Eleanor Boyle is not the first person to compare the fight against climate change to a war. Or even the first to write a book comparing it specifically to World War II. Seth Klein’s 2020 bestseller, A Good War: Mobilizing Canada for the Climate Emergency, explicitly used WWII-era public policy as a guide for the changes we need to make to ward off the climate crisis.

But while she may not be the first, the Vancouver-based food policy writer is uniquely qualified to make the argument laid out in her 2022 book, Mobilize Food! Wartime Inspiration for Environmental Victory Today. Boyle was captivated by the story of how Britain transformed its national food system in service of the war effort. With her backgrounds in journalism, sustainable food policy, and psychology, she’s ideally situated to recount the story of how citizens were convinced to enthusiastically accept the restrictions placed upon them, and connect that history to the possibility of climate-conscious food policy today.

Boyle spoke with Asparagus editor Jessie Johnston about Victory Gardens, inspirational leadership, and the not-at-all radical policy of rationing. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Jessie Johnston: What inspired you to write this book?

Eleanor Boyle: I had been writing about food—especially animal agriculture—and its impact on climate, and coming to feel that climate of our “war.” And discovered the story of how Britain prepared for WWII, in part, by completely redoing its food system in ways that would feed everybody, make the country more self-sufficient, and would help it in winning the war. It was just the most amazing story. And what it told me is that systems can change.

When most people in 2023 think of WWII food policies, they might be familiar with rationing and maybe Victory Gardens. But I know from your book that those were only part of a much larger package of policies. Can you share some of the other changes to the food system that were employed?

One of the thrusts of the programs was Victory Gardens: growing a lot of your own, relocalizing the food system. In terms of the entire country’s agriculture, it was revamped. In the 1930s, Britain’s agriculture was not very productive and was too much oriented to livestock and meat production. And so is ours. It is not a very efficient way of producing food. Animals eat a lot to produce a mere kilogram of meat.

So the government said, “OK. You’re going to plough up a whole bunch of pasture. You’re going to cut down on your livestock numbers. People will still be able to eat meat, but there won’t be quite as much. And we’re going to share it fairly, and we are going to devote more cropland to food for people.” Grains, vegetables, legumes, all those good things.

And one of the themes that comes up a lot is that the changes were mandatory. I know Seth Klein talks about this [in A Good War]. In a crisis, you can’t just ask people politely to please consider wasting less food. Wasting food became illegal. And people were a little ticked off at first at the number of rules that had to be followed. But ultimately, the vast majority were super on board. Basically everybody got fed, which was way better than pre-war, when in Britain half the country had been either undernourished or malnourished.

I’m a huge fan of rationing. I think that for climate, we, Canada, whatever jurisdiction, should consider limiting or giving limited allocations to all of us: of how much we can drive, how much we can fly, and how much meat we can eat. Especially beef. It would be an amazingly effective way of lowering emissions.

What was done to make people accept and even feel enthusiastic about these measures?

How do we effect behaviour change? How do we inspire? How do we rally people to be part of this great project, which is to beat the climate crisis? To change behaviour, you need reasons and you need strategies. Reasons, that’s the education piece. And we all know that that is not enough. Average human beings can hear about things we need to do—that doesn’t necessarily make us do them.

You need strategies that are very specific: “This is what you should do.” I don’t hear much of this from the government. [For example], “Everybody should go three days a week without driving.” We need specifics. We need strategies for how we actually effect behaviour change. That’s number one.

In a crisis, you can’t just ask people politely to please consider wasting less food.

Number two, We need leadership that we can get behind. People who tell us tough realities, but we can tell that they’re being absolutely honest and that they are right. Britain, luckily, had a few of those. They had the Minister of Food, who was amazing. The number one best-known nutritionist in Britain at the time, Marguerite Patten—people loved her. They would flock to the community centres and church basements and people’s homes to hear her talk about how to cook on rations. She was just so likable and so knowledgeable. We need people like that.

You’ve got to have leadership to rally people, to let them what needs to be done, to be honest with them. And then you need specifics that the society can assign to people so that everybody’s involved. Little kids would be out in the garden with their parents and grandparents digging. People need meaningful tasks that really assist in the great project that everyone sees needs to be done.

You touched briefly on Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food. Tell me a little more about him.

Lord Woolton, he was not an elected official; he was plucked from industry and asked if he would please do this. And he was the best kind of leader, which is a reluctant leader. He was a guy who was accustomed to administering huge businesses, but who also had a real heart. He had been a social worker in his youth.

He’d go to soup kitchens and talk to people. He also was a great negotiator. Britain was still importing some foods internationally. The money they had to spend to prosecute the war was unbelievable, and so Lord Woolton had very small budgets to bring in enormous amounts of whatever it was. And he was a tough negotiator.

Charming posters were among the tools the UK government used to rally citizens around its WWII food policies.

The climate crisis doesn’t feel as immediately life-threatening to many people as war did. And the things we’re trying to achieve are different. Which of the policies that you learned about do you think really would translate to making progress on the climate crisis?

My focus is on food. Although it’s not our primary creator of greenhouse gasses today—burning of fossil fuels is—food is up there. Food produces between a quarter and a third of anthropogenic greenhouse gasses.

I think we need more government oversight of food production and also consumption. We have relegated food policy, to a large degree, to corporations. There are—in key sectors like livestock and meat—just a few big owners of mega production facilities, and they have enough power to really set a lot of goals. For example, all the science says, “We can’t eat meat every day anymore.” We don’t have enough planet to produce that. But the big beef companies are on both the defense and the offense to convince people that beef [is] not a climate problem. I think we need to seriously consider breaking up some of those monopolies.

[Haarlem] in the Netherlands, has banned meat advertising in the city centre. The gutsy Netherlands has decided to lower the number of livestock animals in the entire country. Again, you want to eat meat, fine. But we can’t give that much land to animals and that much control to a small number of companies.

We ration things all the time, by price: if you can pay for it you can get it.

And I like the idea of some mandatory measures. I think it could be effective to limit the amounts of meat that people are allowed to eat so that it is within sustainable levels. And I always say there is nothing radical about rationing. We ration things all the time, by price: if you can pay for it you can get it. Which is not the best way to ration goods that produce a lot of greenhouse gasses. Another quick example of rationing: to walk the West Coast Trail, you can’t just go and start walking—you’ve got to apply for a permit. That is a kind of rationing. Because they are protecting the ecosystem.

Behaviour change is tough. There is nothing easy about the shifts that we need to make to beat back the climate crisis. But I think that we will find, if our societies can boldly do the things that need to be done, that it will be more than worth the effort.

If I just look to this small case study, there were benefits that nobody predicted. Nobody thought that health would get better in Britain during the war. But because people were eating less sugar, less processed foods, less meat and more plants, people got healthier. There was less heart disease, there was less diabetes, etc. When you take on a challenge that needs to be taken on, it’s going to be really hard. But it’s also going to produce benefits beyond what we can even see.