From Cattle Farmer to Vegan

In the face of mounting concerns about climate change, one farmer turns vegan. Will others do the same?

Jay Wilde, 62, has lived on a farm his whole life. He started helping out on his family’s beef and dairy farm in Derbyshire, UK, when he was three, readying cows to be milked and feeding young calves. But, as he grew older, he became disillusioned with the industry. In 2017, at the age of 60, he sent his herd to an animal sanctuary and converted the family farm into an organic-vegan farm.

The decision is Wilde’s response to the huge dilemma facing meat and dairy farmers: Many of the industry’s common practices, like intensive farming and mass-importing animal feed, contribute massively to deforestation and the climate crisis. In the face of these challenges, as well as concerns about animal abuse, almost a third of farms across the world are adopting more environmentally friendly practices. Some — like Wilde and his wife — have even gone vegan.

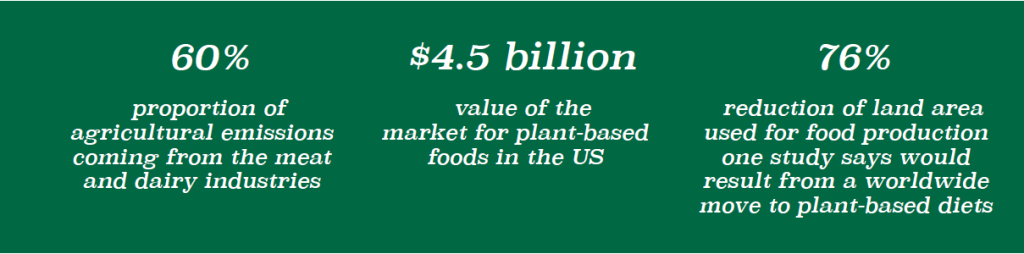

“Globally, about a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions come from the way we produce food,” explains Richard George, head of forests at Greenpeace UK. The way farmers raise animals is a big part of the problem: Animal agriculture, including both livestock and feed production, is responsible for 60% of food-related greenhouse gas emissions, in part through the destruction of forests. Soya production is the second largest driver of deforestation worldwide, as farmers clear trees in South America to make way for the beans, 90% of which are used for animal feed. While the UK imports little beef from the area, it consumes 3.8 million metric tonnes of soya a year, mostly imported from Brazil and Argentina.

The number of people adopting plant-based diets is booming due to climate concerns, and businesses like Morning Glory Cafe in Flagstaff, AZ, are happy to cater to them.

In response to the climate crisis, a growing number of people are turning to plant-based diets. Plant-based foods are a booming business. Veganuary — the challenge of eating a plant-based diet for the month of January — reported over 250,000 participants worldwide in 2019. In the UK, 3.5 million Brits identified as vegan in 2018, up sevenfold from two years earlier, when just over half-a-million Brits said they ate a vegan diet.

“A vegan diet is probably the single biggest way to reduce your impact on planet Earth, not just greenhouse gases, but global acidification, eutrophication, land use, and water use,” Joseph Poore — a doctoral student at the University of Oxford — told the Guardian. He led a 2018 study on the environmental impact of food that was published in the journal Science. The research found that meat and dairy farming provides 18% of calories and 37% of protein worldwide, but uses 83% of global farmland. The United Nations, Greenpeace, the World Wildlife Fund, and British think tank Chatham House are all calling for a global shift toward plant-based diets.

“It’s up to all of us to do what we can to prevent climate breakdown, and that includes eating less meat,” says Greenpeace’s Richard George. But, he argues, far-reaching changes in the food industry are also needed.

Meat and dairy farming provides 18% of calories and 37% of protein worldwide, but uses 83% of global farmland.

Wilde began coming to terms with the environmental hazards of beef and dairy farming at 18, when his interest in natural history and science led him to New Scientist magazine. In its pages, he discovered the environmental impact of the family business.

“I began to read about mounting problems with the environment, including the first discussions about climate change, in particular pollution from burning fossil fuels, ammonia, and nitrate run-off due to agriculture,” Wilde recalls.

Alarmed, Wilde implemented organic principles to reduce the farm’s impact on the environment. As the years passed, Wilde also grew concerned about animal welfare, worrying about cows that seemed distressed in confined winter housing. By 35, he was a vegetarian, although he kept his personal life separate from his dairy farming work.

Jay Wilde grew up on Bradley Nook Farm. Concerned about the planet and animal welfare, he decided in 2017 to convert it from a beef and dairy operation into one growing organic produce.

It was only when Wilde’s father died in 2011, and he took over the family farm, that he felt he had the latitude to make more significant changes. Even then, he struggled to find a clear path forward until 2017, when he had a chance encounter with a volunteer from the Vegan Society, a non-profit that advocates for vegan lifestyles in the UK. The volunteer handed him a copy of the society’s Grow Green report, which discusses how the agriculture and livestock industry can reduce greenhouse emissions and help combat global warming.

“A lot of farmers are born into these situations: they inherit farms, are forced to continue the family business and see no way out of this tough industry,” says Dominika Piasecka, spokesperson for the Vegan Society. “Farming animals is a job around the clock, 365 days a year — it’s physically and mentally exhausting.”

Wilde heaps praise on the Vegan Society, which connected him with people and resources to help him figure out the best way to convert his farm. The Society also helped him find a new home for his 90-strong herd; he kept 17 of the neediest cows, but sent the rest to a sanctuary. The remaining cattle help maintain the ecological value of the farmland by controlling aggressive plant species through grazing. Now, Wilde is planning to build poly-tunnels, greenhouse-like structures that retain heat to extend the growing season and aid the growth of produce.

Wilde isn’t the only dairy farmer to go vegan, though farmers’ reasons vary. An ocean and half a continent away, Andrea Davis turned her dairy-producing goat farm in Colorado into an animal sanctuary. Even though she is a vegetarian, she joined the industry as an intern at a goat dairy in 2009 because of her love of animals. However, she was shocked when she saw mother goats being separated from their kids, as well as when horns were painfully removed from baby goats to make them easier to handle.

The experience inspired Davis to open a “cruelty-free” dairy farm called Broken Shovels Farm. In an effort to treat the animals with love and care, her farm kept non-milking goats as part of the herd, rather than sending them for slaughter as other farms would have done to their “surplus” animals. She also eliminated artificial insemination and the separation of mothers from kids, and provided more comprehensive veterinary care than she’d seen on other farms.

A lot of farmers are born into these situations and see no way out of this tough industry.

Despite the improved conditions, Davis found dairy farming did not align with her views on animal welfare. Perpetually breeding goats to produce milk left them vulnerable to mastitis, a painful disease that infects animals’ udders.

“We had started getting a lot of requests to rescue animals, and I realized it didn’t make sense to breed more when so many needed rescue,” Davis recalls. So, in 2014, Davis and her staff embraced veganism and repurposed the dairy farm as an animal sanctuary. Broken Shovels Farm Sanctuary rescues, rehabilitates and cares for animals, and runs educational programs about non-violent ways of life.

Back in Derbyshire, Wilde plans to showcase the benefits of vegan produce by converting his cow sheds into a restaurant with a cookery school. Both he and Davis are looking to push the food industry forward by educating farmers and consumers alike.

But farmers need support in order to make changes. “The individual changes need to happen,” says Clare Oxborrow, senior food and farming campaigner at the UK branch of Friends of the Earth. “But we need the government and food industry to set up the right framework that will encourage people, and farmers, to eat and farm in the most sustainable way.”

We need the government and food industry to encourage people, and farmers, to eat and farm in the most sustainable way.

With Oxborrow’s comments in mind, Asparagus reached out to the UK’s National Farmers Union with questions about how they’re supporting farmers who want to make their farms more environmentally sustainable. No comment was provided for this article.

“Most farmers would regard [the Vegan Society] as a dangerous enemy,” says Wilde. But he wants to change how veganism is perceived within the industry, and by the general public, in order to protect animals and the environment. Will other farmers follow suit?

Print Issue: Winter/Spring 2020