Trans Prisoners in BC Can’t Get their Day in Court

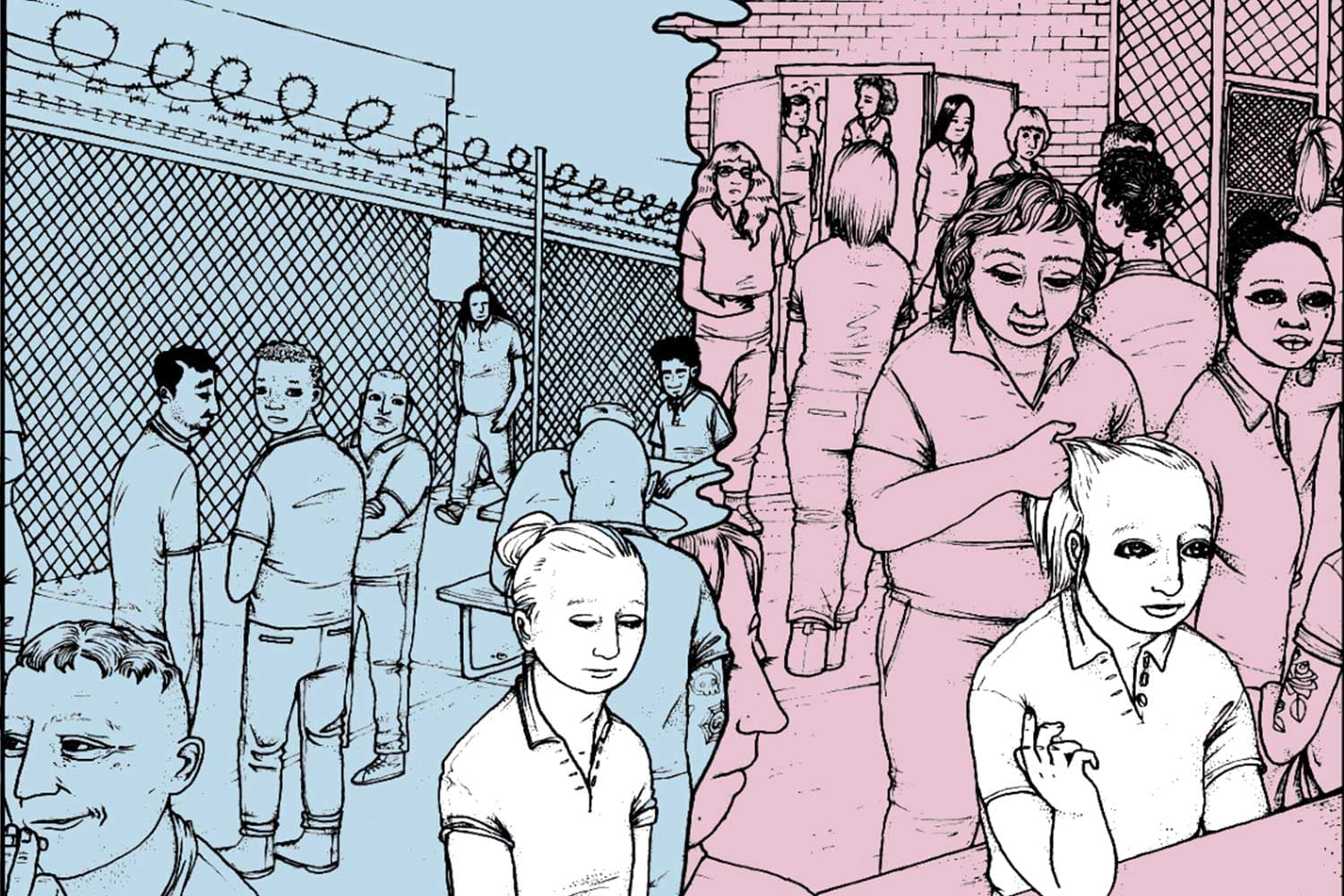

One woman’s story shows how BC Corrections discriminates against trans people.

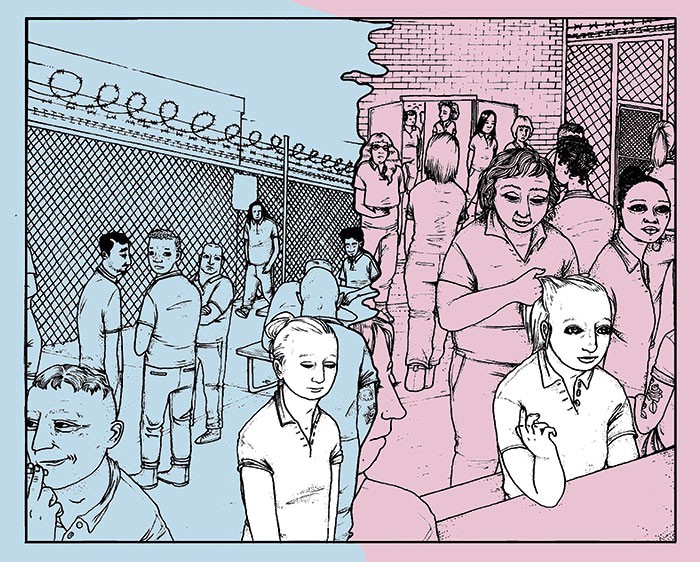

It’s a late May evening at Surrey Pretrial Services Centre — a men’s jail in the suburbs of Vancouver, BC — and Haedyn-Khris Beaumann has had enough. A fellow inmate has spent the past week taunting her with bigoted remarks, and she’s ready to fight back.

“I’m sick and tired of what you’re saying,” she tells him.

The man had been “dropping the F-bomb” (f*g) and insisting that racial and sexual minorities shouldn’t get “special privileges.” He also told her he doesn’t think it’s “right” to be gay.

Beaumann, a pansexual trans woman, had been at Surrey Pretrial since August 2019. She was involuntarily transferred there from the nearby Alouette Correctional Centre for Women, in Maple Ridge. She has filed a human rights complaint against BC Corrections, saying the system discriminated against her as a trans woman by keeping her in a men’s jail.

Since arriving at the men’s institution, she’d faced both sexual harassment and sexual assault. “I just started crying and left. I just couldn’t take it,” said 27-year-old Beaumann of the inmate’s taunts. She went to see her case manager and was placed in a different unit, away from that inmate. But her new unit was under tighter controls; inmates were alone more, with less time out of their cells.

“I’m there until they can figure out what else to do with me,” she said the day after the incident.

Beaumann, who was awaiting extradition to the US on murder and theft charges, said she hoped to be “housed” in a women’s facility south of the border. She and a friend, Christopher Shade, are accused of beating a man to death with a shovel, then stealing his credit cards and vehicle, and fleeing to Canada on a back road.

When she was arrested, she was living as a man. Since then, she’s come out as a trans woman, and joined a long line of transgender people who fought for fair treatment within Canadian prison systems since the 1970s.

Trans people face higher levels of sexual violence behind bars than cisgender people. According to US data collected in 2011–2012, trans prisoners are up to 10 times more likely to be sexually harassed or assaulted than cis prisoners. In the world at large, they also face higher rates of suicide and suicide attempts. Research from 2013 showed that 45% of trans people surveyed in Ontario had attempted suicide, and 77% had seriously considered it.

Trans prisoners are up to 10 times more likely to be sexually harassed or assaulted than cis prisoners.

Beaumann — who is Canadian but grew up in the US — fought her extradition for five years, during which she submitted eight separate legal challenges through the Canadian courts. Her objections to being sent to the US for trial included concerns she might face the death penalty, and fears she wouldn’t be safe as a pansexual trans woman in a US prison. She ultimately lost, and was extradited mid-June. She has been placed in a women’s facility in Washington state while awaiting trial.

Still pending is Beaumann’s human rights complaint against BC Corrections.

Under BC human rights law, prisons are “services” with a duty to protect inmates against harassment and discrimination based on their gender. “They not only have an obligation to protect you from systemic discrimination within the prison, but they also have an obligation to protect you from other prisoners,” says paralegal Shelly Bazuik of Prisoners’ Legal Services, a legal clinic that advocates for incarcerated people. “It’s their obligation to create an environment where a prisoner doesn’t experience discrimination and harassment.” BC Corrections refused requests for an interview.

Bazuik represented Beaumann for five years, and she’s frustrated by the province’s treatment of trans inmates. “If a person’s being sexually harassed a lot, often they’ll end up in a different unit,” she explains. “The solution always seems to be restricting the libterties of the transgender person rather than the person enaged in the discrimination.”

Coming out behind bars

“I’ve known that I was different from a really young age,” Beaumann said over the phone from the men’s jail in Surrey. Growing up, her conservative Christian parents weren’t open to Beaumann being anything but a boy. Her dad refused her pleas for long hair, ballet lessons, and nail polish.

Her parents kicked her out when she was 15 or 16, leading to periods of homelessness. By 19, she’d realized she was trans, and came out to a group of trans people on Facebook. But she didn’t feel safe enough to live as a woman. “I kept it to myself, because I felt that who I was was wrong.”

In 2013, she met Richard Bergesen — the man she’s charged with killing — through her church, and he gave her a place to live. At the time, she was living as a man, with the last name of Patterson. Beaumann alleges Bergesen made unwanted sexual advances toward her shortly before he was killed. Court documents say when Bergesen was found dead in his Sammamish, WA, home in September 2014, he’d been “brutally bludgeoned.”

Court records allege that after Bergesen was killed, Beaumann and Shade stole his car and wallet, and escaped to Canada by driving through a barbed-wire fence. They were arrested in Abbotsford, BC, later that day.

According to court documents, Beaumann has said she’s innocent, and that her friend killed Bergesen. Yet extradition documents say she called two friends shortly after Bergesen was killed and told one, “I fucked up,” and the other, “I hit him over the head with a shovel.” Shade was extradited and found guilty of second degree murder, identity theft, and burglary after pleading guilty in May 2016, and was sentenced to 14 years and 9 months in prison.

There was nobody that I could talk to to figure out who I was.

When Beaumann was arrested and placed among men at Surrey Pretrial, she says she “sealed” her trans identity. Two years on, she tried to come out as trans, but says corrections authorities didn’t believe her. A year later, she met Bianca Bailey Lovado, another trans woman at Surrey Pretrial. “She was really telling me to be myself and to be open,” said Beaumann.

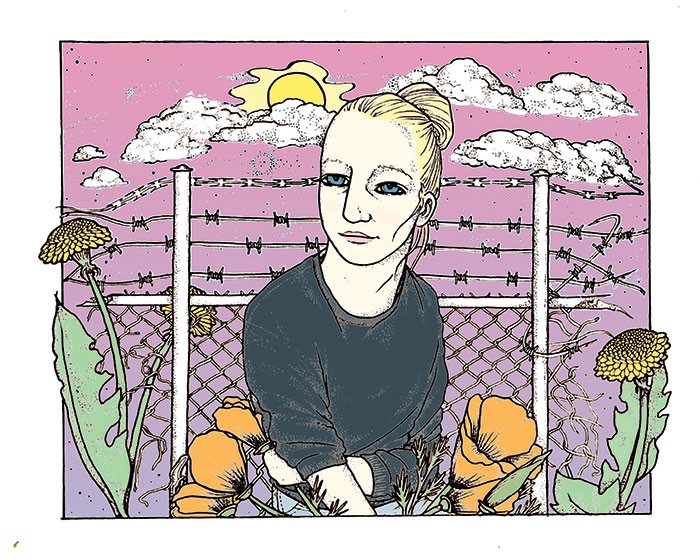

With Lovado’s support, Beaumann tried a second time to come out to the prison administration. This time they took her seriously, and she was able to start hormones to begin her physical transition. But, she says, she didn’t feel there was room to have doubts. “There was nobody here [in a professional capacity] that I could talk to to figure out who I was…I felt nobody wanted to support me.”

“[The warden] said I had to pick if I was [trans]. If they were going to support me, they needed to know who I was.”

After she began transitioning with the help of a doctor, she requested and was granted a transfer to Alouette Correctional Centre for Women. She stayed there for almost a year. Some aspects of her stay were “amazing,” she said: “Everyone accepted me. I was able to connect with a lot of people who were able to show me respect and kindness for who I am.”

“A lot of the inmates helped me braid my hair, helped me learn how to put on makeup properly,” she said. “They cared about me as a person.”

But, Bazuik confirms, Beaumann was under high surveillance at the women’s prison. She felt she went from being seen as a high-risk victim at the men’s jail, to a high-risk predator at Alouette. An officer was assigned to watch her whenever she was out of her cell.

Trans women who haven’t had gender-affirming surgery, like Beaumann, are subjected to more scrutiny than trans women who’ve had surgery, said Bazuik. “An officer [is] following them everywhere they go in the prison as if their genitalia was a weapon… And then, of course, any people who are subject to extra scrutiny end up in extra trouble, just like with racial profiling.” Bazuik says it can also cause fellow prisoners to believe the inmate is being supervised because they’re a sexual predator, regardless of their actual history.

“I dealt with sexual abuse as a child,” Beaumann said. “I would never want to put that on someone…To be labelled as that is so hard, and I eventually broke.”

Beaumann says that when she “broke,” she got into an expletive-laden argument with a guard. A court document describes the incident as “violent.”

People who are subject to extra scrutiny end up in extra trouble.

That argument landed her in segregation, where she stayed for several months before being involuntarily transferred from Alouette back to the men’s prison after another incident in August 2019. A December 2019 court ruling says prison staff had “urgent and legitimate concerns about their inability to protect Alouette’s inmates, its staff, and Ms. [Beaumann] herself after her violent episode.” The judge said because the transfer was an “on the spot” decision, Beaumann wasn’t entitled to advance notice, leaving her with no right to contest the transfer before it happened.

While in segregation, she says she attempted both suicide and genital self-mutilation. In the days before the transfer, Beaumann says she attempted suicide almost daily, and that resisting being put into an anti-suicide smock is what prompted her transfer.

That fall, Beaumann challenged the way the transfer decision was made. A BC judge ruled it was fair for Alouette to make an “on the spot” decision to transfer her back to the men’s jail, but also ruled it was unfair not to provide her with the documented reasons for the transfer until almost three months later. However, the judge did not rule on whether Beaumann had been discriminated against.

Back where she didn’t belong

Other inmates at the Surrey jail didn’t understand what it means to be transgender, Beaumann said. They groped her breasts and teased her for being trans. “They think it’s a joke,” she said. “They think that because I’m transgender I’d like to perform oral sex on them.”

Beaumann’s human rights complaint, filed November 2019, is against BC’s Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, the provincial bodies that oversee BC’s prison system. She wants the BC Human Rights Tribunal to declare that BC Corrections’ decision to move her back to the men’s jail was discriminatory. In the filing, she also asked for financial compensation and to be returned to the women’s prison.

“My dignity, feelings and self-respect have all been damaged as a result of the transfer,” it reads. “I have been assaulted regularly by officers and inmates since my transfer to male population.” It continues: “Since my transfer, I have attempted suicide.”

Although Beaumann was not transferred back to the women’s facility in Canada before her extradition, the American system placed her in a women’s jail when she arrived. Her lawyer in Washington state, Danny Waxwing, says her history of being held at a women’s facility and having received gender-affirming health care through BC Corrections doctors will help her be placed in another women’s institution if she’s found guilty and sentenced.

Prison officials put the onus on transgender prisoners to name the people who are harassing them, when sometimes they’ve been witness to it in the first place.

“She has been very consistent over time that being placed in a women’s prison is what would be safest for her physically, mentally and emotionally,” Waxwing said.

Back in Canada, Bazuik says the Surrey prison is “not at all close to creating a harassment-free environment.” She acknowledges, though, that the institution has “evolved” in the time she has worked with Beaumann. “There’s been five, maybe six [trans] women who’ve stayed at the prison… There’s a core of staff now at Surrey Pretrial who understand what some of the important issues are.”

The current policy does entitle trans people to private showers and bathrooms, and the right to be called by their chosen names. They also have access to gender-affirming health care, though Bazuik says one of her clients once had to wait three months to see the doctor specializing in health care for trans people.

Guards could do more to stop harassment by other inmates, says Bazuik: “The officers still for the most part don’t intervene.” This makes the trans inmate responsible for “ratting” on the person who’s harassing them.

“There’s a whole subculture in prisons about ratting. If you rat on a person, you’re setting yourself up for extra assault and violence,” says Bazuik. “Prison officials are very aware of [this], yet they still put the onus on transgender prisoners to name the people who are harassing them, when sometimes [officials have] been witness to it in the first place.”

Challenging the system

Bazuik wants to challenge BC’s policies on trans prisoners — which don’t automatically give trans people the right to be placed at an institution based on the gender they identify with — in court. What trans people have the right to is a transfer request, which is reviewed by a team made up of medical personnel from Correctional Health Services and deputy wardens from the inmate’s current and requested jails, and may include representatives from BC Corrections headquarters.

The policy gives this team up to 60 days to make a decision. If the transfer request is denied, the process for reconsideration gets arduous. First, the inmate can submit a complaint to BC Corrections and have the request reconsidered, Bazuik says, adding another seven to 30 days to the process. And if BC Corrections still says no, the inmate can ask for a judicial review, which includes getting approved for a legal aid lawyer and having a court hearing scheduled, which can take three more months.

This is an issue, Bazuik says, because the average stay at a BC jail is two months or less. According to the province, the average length of stay is 41 to 61 days in custody, meaning the average trans prisoner will have served all or most of their time before the initial decision is made on their transfer.

Right before her court challenge would have been heard, the prison transferred Beaumann to the women’s jail.

Beaumann tried to challenge the policy in court a couple years back with a judicial review, Bazuik said, but right before the case would have been heard, the prison transferred her to the women’s jail.

One way to change the policy is for an inmate to file a human rights complaint, Bazuik said. This process can take anywhere from six to 20 months. During the human rights hearing, the inmate’s lawyer could ask the tribunal judge whether the timeline for making the decision around a transfer is fair, and the judge could rule that BC Corrections has discriminated and must pay damages to the inmate. This would set a precedent for future trans inmates requesting transfer.

But for inmates who cycle in and out of custody, neither a court challenge nor a human rights complaint can guarantee placement in a gender-appropriate institution. The timing just doesn’t work, Bazuik said. Bianca Lovado, the trans woman who encouraged Beaumann to come out, was transferred to the women’s jail and then released, Bazuik said. She ended up in jail several times after that, but was always placed back in the men’s centre. Lovado died in November.

While still in Canada, Beaumann continued to fight to get back into the women’s jail. When another round of requests were refused this spring due to behavioural concerns, she was so upset she could hardly speak.

“I woke up crying this morning,” she said.

Within days, she was extradited, and placed in general population among women at the King County Correctional Facility. She awaits trial.

Print Issue: Summer/Fall 2020

Print Title: Trans, Inside and Out