In Urban Nature, I’ve Found a Home Away from Home

Among Indigenous elders and my fellow immigrants, I’ve put down roots at a nature center in Northeast Los Angeles.

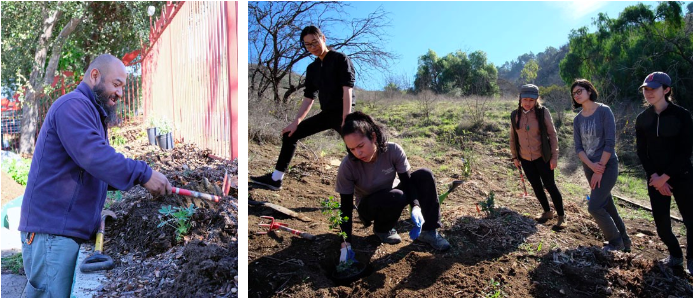

Volunteers at the Audubon Center at Debs Park plant seedlings in the urban oasis they are committed to conserving.

I remember things about my homeland, the Philippines. Life was simple in our country town of Naic, on the big island of Luzon. Every day, I bathed in a tin tub in the yard of the house where I lived with 12 family members. Some days my mother and I perused the stalls of the busy palengke (open-air market) hand-in-hand, inhaling the sweet scent of new stationery and the nose-crinkling smell of fresh-caught fish.

At the beach, I would wade along the shore and watch my grandfather emerge, like a mythic sea god, from a swim in Manila Bay. I remember the dirt roads my father and I jounced along, on a motorbike with a mechanism that played Bach’s Minuet in G major.

When I was 4, my family immigrated to the US, landing on Virginia’s suburban coastal plains. I never felt rooted there, among vacant lots, man-made lakes, and strip malls. Like many immigrant families, we didn’t have the luxury of leisure time to explore the outdoors. My father worked three blue-collar jobs, and my mother woke at 4 every morning to cook for us, before spending 12-hour shifts on an assembly line making electrical wires and cables. They didn’t get to see the light of day, so neither did I, really.

Like many immigrant families, we didn’t have the luxury of leisure time to explore the outdoors.

The moment I could, I fled to the glorious hills, iconic beaches, and vibrant culture of California; I’ve been here 13 years. But much as I love Northeast Los Angeles — flanked by downtown skyline and mountain views — it’s hard to call it home. I never forget that, here, I’m on the land of the Tongva: the first people of the Los Angeles Basin. I long for my past: the one in Naic, and also the one I’ve never known, that my ancestors lived.

I can only trace my lineage back to my great-grandparents, who were each between a quarter and half Spanish. This European DNA seemed a thing of pride in my family. I don’t think any of my relatives ever bothered to unearth the stories of the ancestors who were native to our island, and contributed most of our genes. Almost 400 years of colonization changed our identities as Filipinos. For a lot of us, our homes were no longer in the sacred mountains, rice paddies, and mangroves of my reveries, but in westernized towns and cities. Most of us never looked back.

Three years ago, I started to, in my own way. I decided to redefine home for myself by connecting to the land where I was, since I couldn’t do it in my ancestral home. My local nature center seemed a good place to start, so I volunteered there.

The Audubon Center at Debs Park is a 17-acre park-within-a-park and solar-powered community space, an oasis in the middle of LA’s urban sprawl. Here — where bobcats, coyotes, and white-crowned sparrows dwell among native old-growth black walnut trees, oaks, toyon shrubs, and purple sage — I’ve learned things many of my LA-born-and-bred loved ones either take for granted, or have never known.

Los Angeles sits on the Pacific Flyway and is reportedly the “birdiest” city in the US. Over 520 avian species have been spotted here; 100 of them can be seen within Debs Park’s 282 acres. Northeast LA seems a sensible place for the National Audubon Society to have a foothold, thanks to the San Rafael Hills and the confluence of the Arroyo Seco and Los Angeles Rivers. This topography creates a dynamic habitat and rest area for migratory birds and pollinators.

We were caretakers of the earth. What we took, we had to replace.

The Tongva, including the Hahamog’na band of Northeast LA, have always understood the ecological value of this place, where they thrived for at least 7,000 years pre-contact. “We were caretakers of the earth,” says Tongva elder and activist Gloria Arellanes. “What we took, we had to replace. We made offerings, we said prayers.”

By the late 1700s, Spanish colonizers and missionaries saw the fertile land’s value, too. They set their sights on it to support their own agriculture, and the San Gabriel Mission. Arellanes describes the Tongva’s stories of first contact: “We would loosen the strings on our bows in a non-aggressive gesture, and we expected friendship. And yet, we were enslaved.” Systematically, the Tongva were forced out of their ancestral villages, indoctrinated, and enslaved to build the Mission, established in 1771.

Over the next two centuries, Northeast LA became a suburb. The rivers — once teeming with steelhead trout — were paved over to prevent flooding. A railway and freeway were constructed along the Arroyo Seco, cutting through the grassy hills. The Tongva are still here, but the land and watershed as they knew them are forever changed.

Eventually, zoning laws in the 1940s created more multi-family housing in Northeast LA, attracting Mexican-Americans and eventually Central and South American immigrants. In the last couple of decades, gentrification has brought about more displacement — this time of the Latino families that lived here through the Chicano civil rights movement of the ’60s and ’70s, and the gang wars of the ’80s and ’90s.

Marcos Trinidad is the director of the Audubon Center at Debs Park. His Mexican-American family has lived in Northeast LA for five generations. “There’s a lot of skin in the game for me,” he says. The center allows him to keep a door open for local communities — Indigenous, immigrant, undocumented, and all — to reconcile and connect over something we’re all stakeholders in: the urban nature that surrounds us.

At every opportunity, Trinidad keeps a seat at the table for the Tongva. He’s also spent years fostering a relationship with the Big Pine Paiute Tribe in Owens Valley — the source of most of the water Angelenos drink, use on our lawns, and fill our infinity pools with.

In April 2017, I traveled to Owens Valley with Audubon Center staff and a group of high school students from YouthBuild, a nonprofit that provides job training to underserved young people. Almost all the kids were camping for the first time. Brisk air and golden light against our skin, we pitched our tents by a stream, the snow-capped Sierra Nevada mountains looming like great-grandfathers of the arid valley and the Owens River.

We visited tribal elder Kathy Bancroft at the Paiute Shoshone Cultural Center. Gathered in a circle, we listened as she recounted her ancestors’ history. Their innovative irrigation systems kept the valley lush, letting the Paiute subsist on native plants for millennia.

When settlers displaced the tribe in the 19th century, these traditions were lost. As in virtually all tribal histories, the tragedy didn’t end there. Starting in 1905, Los Angeles purchased a quarter million acres in Owens Valley in order to divert the Owens River from Owens Lake into an aqueduct to support agricultural expansion. The aqueduct was completed in 1913, and the lake was desiccated within 13 years.

Bancroft took us there. From a windswept hill we could only see the smallest sliver of blue amid 100 square miles of barren salt flats. This dry lake bed has been called the country’s largest source of dust pollution by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The dust particles contain carcinogens, and cause lung damage and respiratory disease.

Hearing these stories was a privilege. For those who don’t have the privilege of traveling hundreds of miles, city parks may be their only portal to nature. “Places like Death Valley, Yosemite, Joshua Tree, the ocean — their survival depends on people who live in cities,” says Trinidad. “When you look at legislation and you look at a lot of these environmental laws that are under attack — threatened species and birds, and all these wonderful things that we value — how do we expect to ever make that connection with folks who are not going camping or hiking? How do we expect them to pay into a system that is going to benefit an area that they’re never going to see?”

Places like Death Valley, Yosemite, Joshua Tree, the ocean — their survival depends on people who live in cities.

Showing people that nature exists in their backyard is one way to bridge the gap; inviting them to participate in conservation work is another. A few years ago, Trinidad started to rethink the term “citizen science,” which is how many organizations refer to programs in which the public helps scientists collect and analyze data.

Metropolitan LA is home to 13 million individuals, around 925,000 of them undocumented, according to analysis by Pew Research Center. Since the implications of “citizen science” excluded at least 7% of the local population, Trinidad adopted the term “community science.” Deeohn Ferris — the National Audubon Society’s VP of equity, diversity and inclusion — caught wind of Trinidad’s idea, and insisted the whole organization follow suit.

For me, seeing other brown people at the Center identifying cedar waxwings and yellow-rumped warblers, hearing tribal elders tell their truths, is powerful. It goes deeper than just finding friends who also love the outdoors. I’ve been able to commune with people of color who embody something I couldn’t express before: that we are always connected to nature, because we’re part of it. I can’t lose my sense of home, because the earth is always beneath my feet.

As humans, restoring our relationships to our environment is our only way forward.

I may never get close enough to know where and how my ancestors lived on Luzon, what they did to sustain their homeland. What I can do is care for what I’ve got, where I am, while I’m here. As humans, restoring our relationships to our environment — whether a lush mountain or a concrete jungle, a fish market or a flowing river — is our only way forward. We can learn from the past while working toward a better future, salvaging what we’ve lost ecologically, personally, spiritually. With each bird sighting, every breathless moment under an old oak tree, all the time spent community-building, the seeds are planted; I hope they flourish.

Print Issue: Summer/Fall 2019