Are Buy Nothing Groups a Climate Solution?

Neighbourhood gift economies could help create networks ready to weather the climate crisis.

Buy Nothing groups can provide a space for members to connect and begin fostering neighbourhoods where everyone feels cared for and safe.

The cool summer air of August in Bainbridge Island, WA, washed over Rebecca Rockefeller as she caught a ride to her mechanic. It was 2013, and as a single parent struggling to make ends meet, she was anxious about telling the mechanic she wouldn’t be able to pay for the repairs that day.

But when she arrived, the office assistant smiled, handed her the car keys, and told her she didn’t owe them anything. A group of people had pooled their resources and paid for the repairs, the assistant explained.

Rockefeller recalls that her mechanic was incredulous. “I remember my mechanic, Keith, sitting at his adjacent desk, leaning back in his office chair and shaking his head in disbelief,” she says.

Neighbours freely exchange everything from a pro bono haircut to a child-sized pineapple costume.

Despite the fact that the group had asked to remain anonymous, Rockefeller knew immediately that it was her friends from the local “Buy Nothing” group who had paid. They had even included a bouquet of flowers, which sat atop the hood of her car when she came out of the shop. “I stood in the parking lot crying, realizing that this came from people who three months ago were strangers. It felt like a special once in a lifetime thing,” she says. “I had felt really lonely and vulnerable in the world and now I don’t.”

Buy Nothing groups, hosted primarily on Facebook, expanded rapidly during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. With more than 5 million members in 7,000 groups around the world, the Buy Nothing Project helps growing numbers of neighbours freely exchange goods and services — everything from a pro bono haircut, to a child-sized pineapple costume, to a single serving of homemade soup. As Buy Nothing participants connect with their communities and restore social ties, experts say they may also be building the resiliency needed to weather the storms of climate change.

The connection that created a movement

Neighbours helping neighbours and mutual aid are nothing new, but the formalized Buy Nothing groups sprang up on Facebook thanks to the hard work of Rockefeller and Liesl Clark, who met through their town’s Freecycle group. Freecycle is a website with a similar aim to Buy Nothing, but focused solely on the exchange of goods. Rockefeller and Clark liked to share stories and tell jokes within the descriptions of the things they were giving away, but the local administrator kept reprimanding them for oversharing or exceeding word-count limits. “We were constantly getting in trouble, but we were just having fun and cracking each other up,” Rockefeller says.

The seed that sprouted Buy Nothing was planted when Clark returned from a trip to Nepal and told Rockefeller about a realization she’d had. Clark had visited Himalayan villages and witnessed a gifting economy, where goods are shared without any expectation for recipients to return the favour. As Clark recalls, the act of sharing helped knit the community together.

The act of sharing helped knit the community together.

Rockefeller, who was relying on food stamps to feed her kids, was inspired by the teachings Clark brought back, and the two decided to grow their local gifting economy by hosting a weekly outdoor meet-up. “[I] wanted to be an active participant in my community… Not just taking, but giving back too,” Rockefeller says. Through the group, Rockefeller began receiving food and clothes from other community members, which helped her limited income go further for other essentials.

And when the weather turned cold, they moved the group online to Facebook. Throughout their efforts, they were steadfast about one rule: when you offer an item, or make a post asking for something, you’re not allowed to ask or give anything in return.

Hey there, neighbour!

Rockefeller and Clark were not the only ones inspired by this idea as the project spread to more than 44 countries, creating connection and joy along the way. More than 90 local groups now operate in BC, the majority of which serve neighbourhoods in Metro Vancouver.

One Vancouver resident, Yukti Sehgal, found friendship and generosity through her Buy Nothing group after immigrating from India. She has used the group to meet new neighbours and collect a stash of food containers, which she then uses to distribute home-cooked meals to unhoused people nearby.

“These human connections really do matter,” she says. “It’s easy to rely on yourself, but you need to know that in times of emergency you have someone to reach out to.”

Another Vancouverite, Rina Liddle, used her local Buy Nothing group to connect to her community. When she first arrived in Fairview — a middle-income neighbourhood on Vancouver’s west side — she missed the sense of community she had found in other neighbourhoods.

“When I gave things away, I always invited people in for tea,” she says. “Now I really do feel that I know lots of the neighbours. It gave me a feeling of community.”

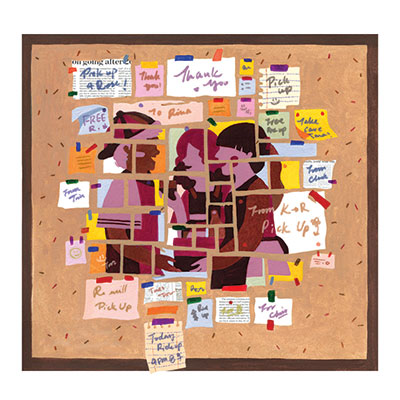

Liddle is now a group moderator, and frequently gives and receives items. She has even compiled the notes she gets from her exchanges into a spontaneous mosaic on the back of her front door. “I just couldn’t bear to throw them away,” she says. The eclectic mix includes flower doodles, smiley faces, hearts, and embellished text that reads “To the one and only lovely Rina.”

The climate connection

Many members of Buy Nothing groups would affirm that the movement is rooted in environmental sustainability. On the surface, this makes sense because they reduce waste and material consumption through the free exchange of otherwise unwanted goods. But the groups’ power to forge connections between neighbours has important environmental implications, too.

I moved to Vancouver from Coquitlam (a nearby suburb) in the summer of 2021. I had just graduated from university, and I wanted to explore the city and meet new people. Many Covid-19 restrictions had just been loosened, and social connections should have been easy to come by, but I struggled. I didn’t know how to approach my neighbours or make friends with the people in my building.

My experience is not unique: Recent research shows that loneliness is on the rise, and in 2020 76% of Canadians were found to have experienced loneliness. It’s a statistic that’s particularly concerning when we look at how climate change affects individuals and communities. Research shows that people who have strong social ties within their communities are more likely to survive natural disasters — from hurricanes to earthquakes to heat waves. Alice Henry, an associate of the environmental think-and-do tank OneEarth, has found that connection not only increases resiliency, it can also embolden people to take a stand.

“Small interactions change how people feel about their sense of community,” Henry says.

“When an individual thinks about the crazy huge problem of climate change, they’re more likely to experience eco-anxiety and paralysis,” she says. “But being connected to your community, it begins to open up that feeling in the face of climate change that ‘Maybe I can’t do much just on my own, but we can do things together.’”

More connected communities could be a life-saving climate solution.

This fact hits home when I consider the record-high temperatures that hit BC this past summer, killing 569 people. The majority of them were seniors. Scientists estimated the heat wave would have been at least 150 times less likely to occur without human-caused climate change.

At a convention shortly after the heat wave, Dr. Sarah Henderson from the BC Centre for Disease Control said that most heat-related deaths in the community happened in private residences. The neighbourhoods where people were most likely to die had a lack of green space, more people living alone, and low income levels.

If, as this suggests, isolation factors heavily in deaths during climate emergencies, then more connected communities could be a life-saving climate solution. OneEarth’s Henry certainly thinks so. “It makes a difference when you’re relying on your neighbours,” she says. “It maintains community connections when there is a disaster.”

Nothing is apolitical

Buy Nothing groups knit communities together, but threads of societal inequity and discrimination can be woven into their fabric as well. The groups may seem apolitical, but their structure prioritizes access for certain people, and can unintentionally exclude those who may need community support the most.

Raagini Appadurai, an equity, diversity and inclusion consultant, recommends looking for barriers to access when assessing how inclusive a community space may be. To have success in a Buy Nothing group, a person needs a consistent home in the neighbourhood, reliable internet access, mobility to get around, a decent level of English, time to spend on Facebook, and comfort with sharing their name and location with relative strangers. This tips the scale of access towards financially stable and able-bodied white people who have the privilege of not considering how racism might factor in their community interactions. And while not all group members fit this definition, their presence looms large.

The Buy Nothing co-founders themselves came to recognize these flaws, and have encouraged local groups and their administrators (known as “admins”) to address the ways inequity and racism affect gifting. In a June 2020 open letter, Clark and Rockefeller wrote “Each group has the power to dive into its own history, boundaries, rules, and culture to improve and build a better, stronger, anti-racist gift economy.”

Who is missing from this space? Are we listening to marginalized voices?

Appadurai says it’s critical that white people reflect on how racism and exclusion can be built into communities such as Buy Nothing. “If privileged populations continuously engage in things like Buy Nothing without having the anti-bias awareness of privilege and oppression conversations, [an] awareness of white supremacy, and systemic racism, that perpetuates harm,” she says. “Whatever barriers, walls, mentalities, biases that are in the way of us accessing each other and working together…those are the things we need to bring down.”

Clark and Rockefeller’s open letter suggests questions for Buy Nothing admins and members to reflect on and discuss, including whether a group’s geographic boundaries replicate official or unofficial segregation lines. For example, many groups operate within their city’s existing neighbourhood boundaries, which may entrench divisions between areas with different income levels.

These divisions can be reinforced when a group gets too big and splits into two or more new groups. In the Buy Nothing world, this is referred to as “sprouting.” Rockefeller and Clark’s guidelines recommend about 500 to 800 members for a strong community spirit within the group. And it’s sage advice: Many group admins say they see a decrease in the gifting ethos as a group grows, and an increase in people who simply want to get rid of stuff as quickly as possible.

When Vancouver’s Grandview-Woodland Buy Nothing group sprouted, the preparation included asking the community for input, and polling members. The group evenly divided the number of members into three smaller groups.

But a member of one of the new groups, Jennifer Gauthier, has observed the new boundaries creating inequality. The area with a higher concentration of large detached homes is now separated from her area of mainly apartments. Gauthier says that she’s seen a decrease in offerings of high-quality items, and increased demand when they do come up in the new group. She suspects it may be due to income differences between the areas.

The power imbalance between admins and members also poses a fairness challenge. Due to the way Facebook groups are set up, admins have significant authority over their groups. “[Being] an admin who has control [of] who gets in and who has to stay out sets people into a position of power over their communities that can be problematic,” Rockefeller says.

Each group has the power to dive into its own history, boundaries, and culture to build an anti-racist gift economy.

The Buy Nothing Project launched a mobile app in fall 2021 that eliminates the need for admins and allows users to choose their own neighbourhood boundaries, which may help to tackle some of the issues. It is too soon to say, though, if the app is making Buy Nothing more inclusive.

It’s clear the Buy Nothing model does not work for everyone. But similar gifting groups are springing up with different names and rules that fit the communities creating them. Kimberley Wong, a community organizer based in Vancouver, says that as a queer Chinese-Canadian femme, they don’t feel safe in their neighbourhood’s Buy Nothing group. Instead, they’re part of the Vancouver Queer Spoon Share, which was built with a disability justice lens and a spirit of freely giving not only things, but also a helping hand and emotional support. Wong explained that they feel more comfortable in this group due to members often having shared experiences and values.

And, of course, gift economies already exist in many cultures and don’t need an online group to continue operating. In a chapter of the book Indigenous Spiritualities at Work, father and daughter Dara and Patrick Kelly — from the Leq’á:mel First Nation — describe how gifting has helped the Stó:lō people thrive for thousands of years: “The gift economy shapes our integrated system of spiritual, social, symbolic, and practical exchanges.”

The basics: food, water, shelter, community

Gift economies, Buy Nothing groups, and their online and in-person counterparts share a common thread: care. Care for each other and the planet are both necessities for today’s fight against climate change, and tomorrow’s efforts to survive it. But marginalized groups are most likely to experience the impacts of climate change, which can be worsened due to a lack of community acceptance and inclusion. And despite the fact that Buy Nothing groups can provide a low-barrier opportunity for some to find belonging and kinship in their neighbourhood, they don’t yet function that way for everyone.

From her experience in consulting on equity and inclusion, Appadurai recommends that groups ask critical questions such as, “Who is missing from this space? Are we listening to marginalized voices? Are we creating space for discomfort and new knowledge?”

These groups alone cannot provide the connections necessary for resilience in the face of climate change. The seniors that perished in the summer 2021 heat wave come to mind. Were they in their local Buy Nothing groups? Would that have been enough to save them?

Without conscious consideration, these groups can reproduce the inequities already threaded through society. When thoughtfully and inclusively created, Buy Nothing groups can provide a space for members to connect and begin fostering neighbourhoods where everyone feels cared for and safe, which we will all need in the coming years.

“Human nature is innately generous, and we recognize that none of us survives alone,” says Rockefeller. “We need community to survive.”

Print Issue: Spring 2022

Print Title: Buy Nothing, Build Community