Protect the Amazon Rainforest by Eating These 5 Foods

Cattle ranchers keep burning the Amazon, but supporting sustainable food producers can help conserve it.

The Amazon’s best-known export, açaí berries are in demand around the world.

These days, the word “Amazon” brings ecommerce to mind more often than the world’s largest tropical rainforest, which is under threat once again from raging fires driven by record levels of forest clearing for cattle ranching and soy production. Unlikely though it sounds, however, commerce could actually be a way to save the Amazon.

We tend to think of the Amazon rainforest as one thing: an impossibly large expanse of green. But what best defines it is diversity. Its 7.8 million hectares spread across nine countries are home to more than 30 million people, who between them speak over 300 languages. The flora and fauna comprise 10% of the world’s known species, and there are plenty we don’t yet know. Its economies are diverse, too, from the large-scale logging, cattle ranching, soy cultivation, and mining that have already destroyed a fifth of the forest, to traditional agricultural systems that integrate with the Amazon’s ecosystems.

As Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro strips environmental protections and Indigenous rights, and encourages illegal loggers and miners to invade protected lands, people outside Brazil wonder how they can help. Those unable to vote Bolsonaro out at the polls can vote for forest conservation with our wallets, whether by investing in funds divested from deforestation, or demanding that local retailers boycott beef and soy linked to forest clearing — Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of both.

The more we can support traditional agricultural systems, the more we’re stabilizing the forest frontier.

We can also buy foods whose production protects the Amazon. “The more we can support local communities to maintain their traditional agricultural systems, the more we’re stabilizing the forest frontier,” explains Jacob Olander, who founded Canopy Bridge, a crowd-buying mechanism connecting small producers in the Amazon with global markets. It’s among a growing number of companies and NGOs working to preserve the forest by realizing the economic potential of sustainable industries within it.

Consumers around the world can be part of that equation by buying sustainably harvested forest products, from foods to cosmetics. “If you condemn Amazon communities to only selling their products locally, then you’re losing a huge opportunity to do good,” says Olander, who believes the climate benefit of supporting forest-protecting industries far outweighs the emissions of shipping abroad.

“If you think about conserving the forest,” says Fernanda Carvalho Stefani, “you have to think about biodiversity.” Stefani’s trading company, 100% Amazonia, exports 25 sustainably sourced Amazonian ingredients to 60 countries as oils, butters, pulps, and powders. She argues that if Amazon supporters focus on only one product, growers are incentivized to replace natural ecosystems with monoculture.

“Having a global audience… can help support more diverse production systems,” says Olander from Canopy Bridge. “But it’s a big challenge, as those traditional systems are based on diversity and flexibility, and markets tend to demand predictability.”

If Amazon supporters focus on only one product, growers are incentivized to replace natural ecosystems with monoculture.

Another challenge is knowing whether products are truly sustainable, as supply chains in the Amazon tend to be long and complex. Environmental and social responsibility certifications such as FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) and Rainforest Alliance can be prohibitively expensive for remote communities, though they are a good starting point when buying from larger brands. Local certifications such as Origens Brasil — an initiative that connects companies to sustainable producers in conservation areas — also help consumers make informed, ethical choices.

And it’s worth the effort, as there’s a world of interesting flavours waiting to be discovered. The five foods below only scratch the surface, but are a great place to start.

Guaraná

When guaraná berries ripen, their white-coated seeds burst out of orangey-red skins. Around 2,500 metric tonnes of the caffeine-rich fruit are harvested each year, hundreds of which are made into Brazil’s answer to Coke, Guaraná Antartica. Drinks company Ambev’s middlemen are among the fruit’s main buyers, but often pay growers the bare minimum.

The ripe guaraná berry’s uncanny resemblance to an eyeball forms part of the origin story of the Indigenous Sateré-Mawé people.

Indigenous groups in the Amazon were trading guaraná centuries before Ambev, however. The Sateré-Mawé people are credited with domesticating the wild vine, and creating a method for preserving the seeds that’s still used today. For the Sateré-Mawé, guaraná is so much more than a livelihood. It’s their mythology, their identity, and also a beverage they make by roasting and grinding guaraná seeds into a powder that gets formed into sticks, then grated into water.

Global interest in guaraná is growing due to its reputation as a stimulant, digestion aid, and aphrodisiac. The Sateré-Mawé and other Indigenous growers have formed associations to seek organic certifications and negotiate more equitable prices.

“You’re supporting and enjoying a traditional culture,” says Stefani from 100% Amazonia, who travels deep into the forest to buy guaraná from an Indigenous cooperative for US health brand Alovitox.

Chocolate

A more familiar Amazon product is cacau, or cocoa, the raw ingredient for chocolate. Cocoa has been cultivated there for millennia, and there are thousands of wild Amazonian cocoa varieties.

In the past five years, the single-origin chocolate boom has given rise to brands producing premium Amazonian chocolates through direct relationships with farmers. Na’Kau started working with wild Amazonian cocoa in 2013. The company says it now sources cocoa from thousands of harvesters across the Amazon, providing community training to improve the cocoa quality. Check the Culinary Culture Connections website for their dark chocolate bars studded with Amazonian chilies, fruits, and nuts.

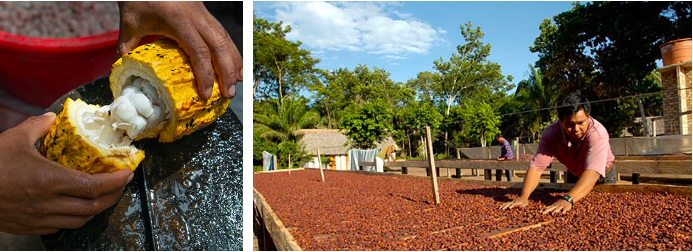

An Amazonian cocoa fruit is cracked open to reveal its seeds. (L) Cocoa farmers dry cocoa beans in the sun in Bení, Bolivia. (R)

A number of other Amazonian chocolate brands are available for purchase in North America. Brazilian bean-to-bar chocolate maker Luisa Abram works closely with riverside communities in the Amazon, teaching cocoa growers fermentation techniques that add value to their beans. Chocolate maker César de Mendes used similar strategies to launch a bar last year made from cocoa grown and processed by the persecuted Ye’kwana and Yanomami Indigenous peoples. The intense 69% cacau bar sold out at its launch event in São Paulo late last year.

Conservation is a key ingredient in the chocolate made by Original Beans. Their team journeys to remote African and South American tropical forests to source rare cocoa varieties, and helps protect them through replanting initiatives. For a taste of unique Amazonian cocoa, look for their Beni Wild Harvest bar from Bolivia and the Cusco Chuncho bar from Peru’s Sacred Valley.

Brazil nuts

A Simpsons episode set in Brazil was so heavy on mixed-up stereotypes even the Brazilian president at the time rebuked it. However, one line about Brazil nuts — “We just call them nuts here” — gave Brazilians something to aspire to. Because there’s actually an ongoing debate about whether to call them castanha-do-Pará , castanha-da-Amazônia, or castanha-do-Brasil (nut from Pará State, the Amazon, or Brazil, respectively).

People do agree, though, that consuming them helps conserve the Amazon, thanks to the way they’re grown and harvested. Coconut-sized seed pods take up to a year to mature, then fall to the forest floor where they’re gathered by hand and cracked to reveal a puzzle of stacked seeds. This wild harvesting is done largely by forest communities living in rare ecosystems that are vulnerable to the lucrative lure of turning forest into pasture. Generating income from a sustainably managed activity that prevents deforestation is a win-win for these communities and the forest.

A harvester cracks open Brazil nut pods that have fallen to the forest floor. Inside the pods, seeds are stacked like three-dimensional puzzle pieces.

Recent initiatives have helped implement harvesting practices that better protect the trees’ natural regeneration cycle, while improved storage, drying, and transportation methods have raised the quality of nuts for export. Cooperatives have also formed to help regulate prices, providing a higher income for the harvesters. Brazil’s Acre state, for example, is still 88% Amazonian rainforest, and the creation of rural producer cooperatives generates income for thousands of families without harming the environment.

Baniwa chili powder

Just a small pinch of Baniwa chili powder packs a powerful punch. The spice mix is made by the Baniwa people, who have lived around the upper Rio Negro near Brazil’s border with Colombia for as long as 3,000 years. Domesticating chilies has been part of their culture for millennia, too, with over 70 varieties growing in the region.

Brazil’s Instituto Socioambiental — an NGO promoting Indigenous cultures — started working with the Baniwa in 2005 to commercialize the spice mix as an income source for Baniwa women. The potent blend is made with dozens of different peppers that are dried and ground with salt, and sold online by Culinary Culture Connections.

Baniwa women harvest Amazonian chilies that will be ground up with salt and sold around the world. The chilies form part of an important agricultural system in the Rio Negro region that now has a protected heritage status in Brazil.

Brazilian celebrity chef Alex Atala has also been a champion of Baniwa chili, which featured in an episode of the Netflix series Chef’s Table. After watching the episode, the founders of Irish microbrewery Hopfully Brewing Co were inspired to launch a series of brews using Baniwa chili, from a spicy farmhouse ale to a weiss beer with white chocolate and coconut. In an email, they said they gave 10% of the chili beer sales back to the Baniwa community.

Leticia and Peter Feddersen created Soul Brasil in 2018 to bottle Brazilian biodiversity in a range of hot sauces and jellies. “Everywhere we travel, we see foods from all around the world — except from Brazil,” says Leticia. Soul Brasil blends Baniwa chili with organic açaí to make a hot sauce with all-Amazonian flavours.

Açaí

Speaking of açaí, these berries are arguably the Amazon’s most famous product, generating around US$95 million per year in revenue for Brazil, the world’s largest grower. Native to the Amazon, açaí palms in season are laden with dark purple berries that hang from fronds like a mop of knotted hair. Brazil produces more than a million metric tonnes of the fruit pulp per year, and its “superfood” health credentials have conquered the world.

Açaí palms are native to the Amazon rainforest. The nutritious fruit pulp is traditionally eaten with fried fish, or sprinkled with tapioca or toasted manioc flour.

The global açaí craze has been a mixed blessing for the Amazon, though. On the positive side, demand for the fruit has made forest where it grows more valuable standing than cut down for palm-heart farming or pasture. But it has also given rise to monoculture, damaging not just the forest ecosystem, but farmers’ revenues — as less ecosystem diversity hurts pollinator populations, which leads to lower fruit yields, a recent study showed.

“Açaí monoculture is of course not as bad as deforestation for pasture,” says Fernanda Stefani from 100% Amazonia. “But native açaí has the potential to preserve the forest when there is agroforestry management in place.” Agroforestry systems protect biodiversity through small-scale farming that works in harmony with the forest ecosystem.

Certifications by the Rainforest Alliance or FSC can also indicate the açaí is more sustainable, though they can also give a false impression. “Greenwashing is very common in the large açaí companies, because of the volume they buy,” explains Stefani, who worked as an açaí exporter for 14 years. “Certifying all of it requires more resources than they make available.” So companies with certifications may not only be selling certified berries.

There are few açaí brands with transparent and sustainable supply chains. Leaders in this realm include Awi Superfoods, 100% Amazonia, and Amazonbai, the first açaí brand to receive FSC certification. Botanica Origins is set to launch in the USA in late 2020, selling sustainably sourced açaí among other forest ingredients. Perhaps more will follow, if consumers are willing to demand — and pay a premium for — sustainability.

Brazilians cannot conserve the Amazon alone, especially while Bolsonaro is in power. We can all help protect the forest’s vital role in limiting climate change, but doing so needn’t be driven by guilt. To put Amazonian foods on our plates is to taste the forest’s biodiversity — a whole world of ancient flavours. And to demand those foods be sustainably sourced means boosting Amazonian economies while protecting the forest.