Finding our Way Past Trading Posts

Art markets in the US Southwest can be spaces of pain for the Indigenous people whose cultural artifacts they sell.

Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, AZ

When I was a child living on the Navajo Nation, I’d ride along on trips to nearby border towns in New Mexico with my parents and grandparents. My sister and I would be in the back seat of my dad or grandfather’s old pickup truck, sharing snacks, playing, or napping as we made the 45-minute journey to Gallup, NM. Sometimes we would detour to the trading posts and pawn shops downtown.

As we approached the trading posts, my eyes would be drawn to the tall windows and the massive Diné weavings I could see through them (Diné is the name our nation uses for ourselves). The walls were covered in art, wooden dolls representing Zuni and Hopi kachinas (spiritual deities) were arranged in dancing scenes, countless pieces of silver jewelry sat neatly placed on pedestals. Baskets were stacked and elegantly displayed, and other forms of Indigenous expressive culture were arranged so precisely I could rarely see any empty wall or floor space.

Trading posts have long done harm under the guise of supporting communities.

I recall the smell of leather saddles, moccasins, hides, and bridles. Antique wooden furniture would be covered by piles of Diné weavings and horse blankets. Taxidermy animals and hides hung high up on the walls. All around the room, glass cases displayed hundreds upon hundreds of precious stones and antique Indigenous-made jewelry.

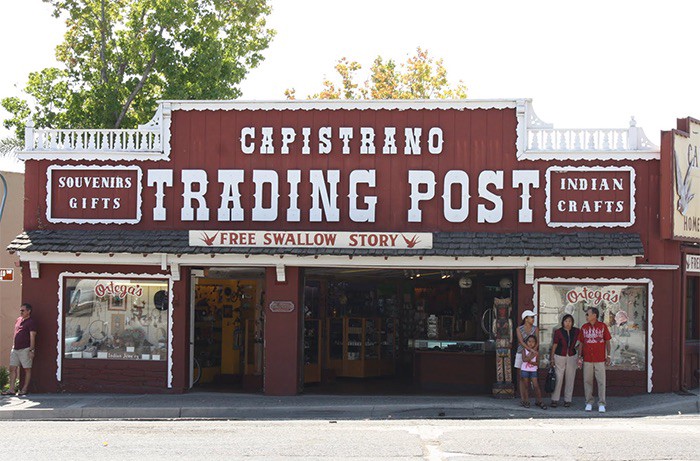

Establishments like this dot the southwestern US. They’re mostly owned by non-Indigenous settlers who purchase goods from local Indigenous artisans and craftspeople at rock-bottom prices and resell them for a profit. With few work alternatives, talented Indigenous artisans reproduce their nations’ culturally sacred items without ever earning a comfortable living. Trading posts have long done harm under the guise of supporting communities. But the Covid-19 pandemic has broken some of those patterns, exposed the harms, and opened the door for Indigenous artisans to use the digital realm and Indigenous-led efforts to share their work with the world.

Trading posts were first established by settlers in the mid-to-late 19th century, to foster economic trade between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Typically, Indigenous people would trade handcrafted jewelry, textiles, baskets, and other goods in exchange for food, enamelware, fabric, manufactured wool, tools, saddles, and other necessities. The development of capitalism, industry, and reservations as part of westward expansion altered social relations and created a brand new market for “Indian-made goods.” Trading posts were an integral feature and facilitator of these changes.

Historically, trading posts played a major role in the expansion of Indigenous art markets in the southwestern US, which shaped popular ideas, myths, and stereotypes about the region and the tribes who inhabit it. Those who shop at trading posts may falsely believe that the items for sale have been ethically acquired, and that the shops have established friendly relationships that support Indigenous communities.

Ortega’s Capistrano Trading Post, in San Juan Capistrano, CA

In fact, the posts take advantage of people who have been systemically impoverished through colonial policy, forcing them to create and sell items of personal, familial, and spiritual value. The posts also fail to honor the countless individual creators and knowledge-holders whose talents they benefit from, and the generations of Indigenous people who have passed through these spaces as a means of survival, to share their craft, or to search for their family’s heirlooms.

For non-Indigenous tourists, trading posts and pawn shops are spaces where they can indulge in Indigenous culture. But for the Indigenous people who frequent the shops, these are often spaces of memory and loss where their tribe’s objects are being pawned, traded, or sold, stirring complicated, painful, and overwhelming emotions.

Trading posts fail to honor the countless individual creators and knowledge-holders whose talents they benefit from.

My sensory memory of trading posts is intimately tied to my childhood sense of wonder. As a kid, I constantly questioned older family members about who made the objects being sold, and why they ended up in trading posts.

My family taught me the value and meaning behind various pieces of our regalia, family heirlooms, and the sacred items we use to protect our families and homes. When I had my kinaaldá (coming of age ceremony), I received my first basket to hold and protect my jewelry, medicine bags, and cultural treasures. So when I saw our baskets for sale — far from their homes and families — it stirred difficult questions in me. More than that, I wondered who would care for them and where they would find their final resting place.

Many trading posts advertise Indigenous, antique goods as “authentic,” perpetuating the idea that Indigenous cultures are frozen in time. Non-Indigenous people then treat living, breathing Indigenous people as objects of the past and colonial subjects. For the non-Indigenous consumer, these Indigenous-made crafts do not come from sovereign nations with distinct cultures and languages, or any ounce of autonomy or agency. They’re just artifacts from a distant past.

In recent years, mainstream media has increased coverage of Indigenous communities and issues, which in theory could counteract this ignorance. But there can be negative consequences to this effort. For example, non-Indigenous led or owned entities will seek to exploit issues in our communities to further their own business profits or organizational agendas.

The Navajo Nation and other nearby Indigenous nations and communities were hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. Not only did individuals’ health suffer, but many families faced dangerous economic impacts. Tribal leaders, activists, youth, and grassroots organizations have stepped up and gathered resources to support those most at risk.

But in Gallup, the owners of trading posts and pawn shops were more concerned with losing revenue from low inventories and staff shortages. In July 2021, Albuquerque TV station KRQE interviewed shop owners about the impact Covid-19 has had on their businesses. Journalist Jackie Kent reported that “a few shops in Gallup say they’re hopeful more artists will return to work once the unemployment bonuses go away in September.”

Trading posts on the reservation and in border-towns — which are major economic centers along and outside reservation boundaries — have a particular historical importance. Beyond that, and considering all the points above, what purpose do trading posts serve? And who do they ultimately serve and benefit?

I imagine a future art market that creates a foundation for sustaining our traditional knowledge and cultures.

The trading posts that are recognized as National Historic Sites help us understand the material, social, and economic conditions and relationships within the southwest region. But if, instead of looking at them historically, we consider trading posts as active sites of capitalist exploitation in the present, it is clear we must move forward toward a different model.

If we consider the depth and importance of these questions and our ongoing relationship with trading posts, I believe we can come to a place where we put Indigenous people first and create our own self-sustaining and self-sufficient Native founded and led cultural art markets that truly benefit Indigenous artisans. I imagine a future, self-sustaining art market that not only supports Native people and communities, but that creates a foundation for sustaining our traditional knowledge, languages, and cultures. Where we can practice art and dance, speak and teach our languages, and nurture future generations in taking on this project.

There are a number of grassroots organizers, artists and musicians, culture-bearers, and mutual aid groups who’ve begun to establish networks and sites of trade that are economically sustainable, community-oriented, and focus on the well-being of land, spirit, and people. I hope that in recognizing the harmful history of exploitative trade in the Southwest, we can begin to build each other up from the center, rather than from the periphery. I hope we can cast aside the idea that we need someone to save our cultures from disappearing: Since time immemorial we have been here, and we have the power to support an art market that allows our people to flourish.

Print Issue: Fall/Winter 2021

Print Title: Unfair Trade