It’s Not Easy Being Green Outside the Big City

When work took me out of my urban bubble, I saw how inconvenient living green can be.

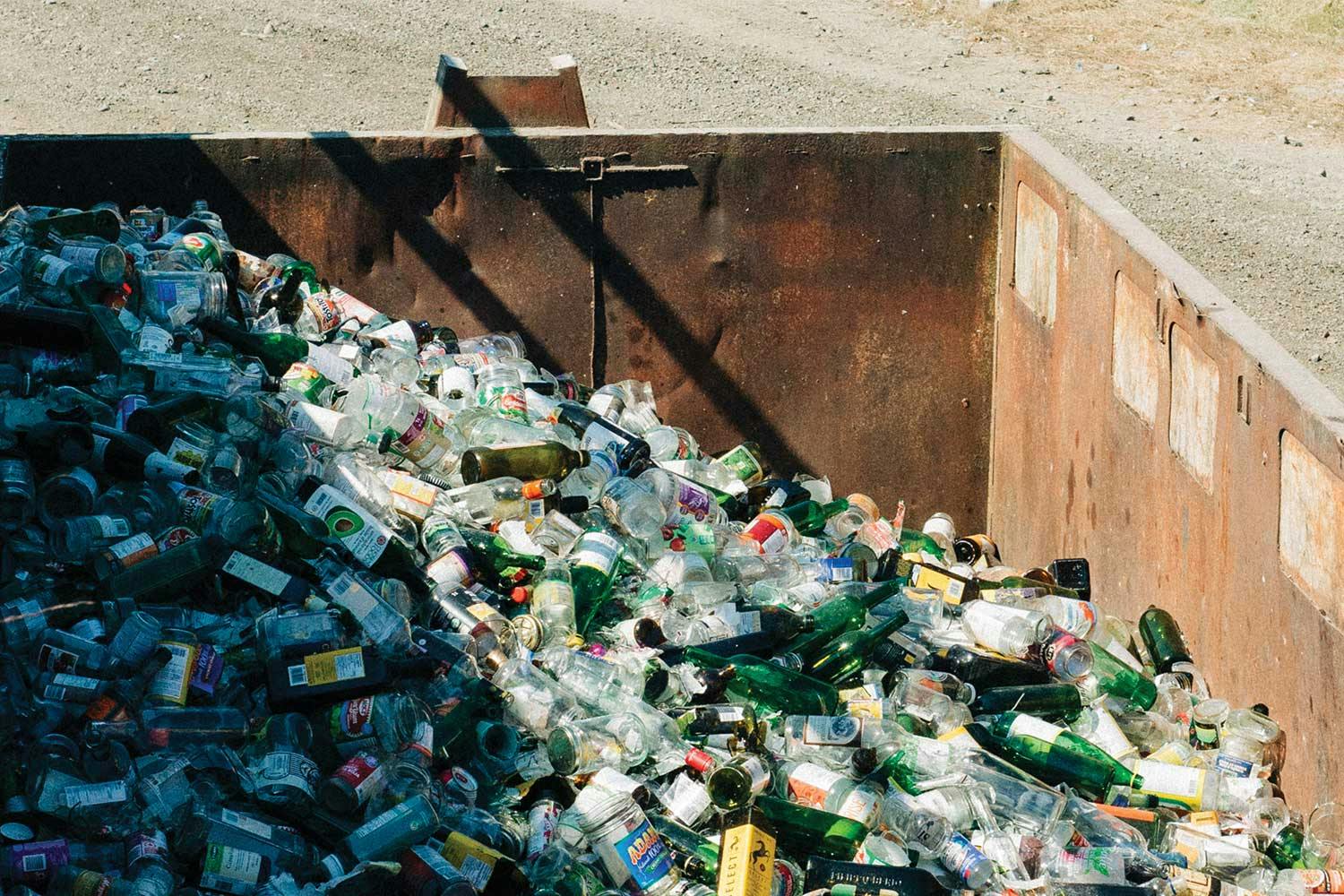

In Duncan, BC, residents must deliver their glass for recycling to the local depot.

Too much of my identity is caught up in the fact that I’m a recycler. I know that most plastic bottles do not make it to recycling. I know that there are entire industries that cause more destruction to the planet than I’ll ever cause in my life, and that me recycling won’t be able to balance it out.

But I have been flattening cardboard boxes, rinsing tin cans, and putting milk jugs into a blue bin since the early 90s. Maybe because I was indoctrinated with “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” messaging. But also maybe because I want to believe that I can help. I want to believe that my efforts will not be in vain, that others will see my “good deeds,” and they will care about the planet as well. Our society produces so much waste. And recycling, while not perfect, is better than adding to our growing landfills and ocean garbage patches.

“If it was ever alive, it can be composted,” says my friend Keli Westgate. “If it’s not plastic, metal or glass, it can be composted. And plastic, metal and glass can be recycled. There’s not much left that should go to a landfill.” Heck ya, Keli!

This spring I had a six-week contract in Prince George, BC—a city of about 80,000 people, a nine-hour drive north of Vancouver—and was staying in a motel room with a kitchen. I quickly realized there was no blue bin for my recyclables, so instead I cleaned them and left them to the side of the garbage. Because who in their right Environmentalist-from-Hell mind would throw out recyclable items?!

After a week or two of doing this, I was informed that I should just put them into the garbage, because that’s what the cleaners did with them. I was confused. On the walks I’d taken around the small city, I’d seen blue bins outside multiple homes.

The moment I threw a tin soup can into the garbage bin, my brain scrambled. It was like I was wearing my bra backwards, weird and pointless. It felt like I was committing a mortal sin. HOW COULD I?

Even worse than putting plastics in the garbage bin was discarding my compostables. So gross! I squirmed when I scraped bits of broccoli and quinoa, pasta sauce and stale bread on top of plastic containers, tin cans, and glass jars. My brain is so conditioned to separate out my waste, that the idea of paper, plastic, and food scraps going into the same bin gives my body that nails-on-a-chalkboard feeling. Just no.

Smaller places haven’t been set up for the same kind of sustainable success.

Then I remembered that Vernon, BC—the small city where my mother lives, known for its plentiful supply of local fresh fruit and vegetables—only started municipal compost of food waste in May of 2022. I had to check my privilege more than once when I was in Prince George. I was a Big City girl with lots of access to programs and facilities. Vancouver’s Zero Waste Centre—where residents can drop off things like cardboard, styrofoam, old clothing, used lighting, and more—is only 4 km from my house. I can take transit there. A London Drugs 1.5 km from my house has a station where I can drop off used batteries, small appliances, and soft plastics for recycling. It’s all so accessible here.

In Prince George, however, people looked at me funny when I wanted to walk 20 minutes to work. Which makes sense, because it wasn’t the safest route walking on the side of the highway. But transit wasn’t very frequent, and my body and mind are used to the routine of making sustainable choices. The populations of many smaller places haven’t been set up for the same kind of sustainable success.

A 2011 government regulation mandating that industry take responsibility for the packaging BC residents throw out resulted in the creation of a provincial non-profit called Recycle BC. It’s supposed to help communities manage residential recycling. Knowing this, I made an ass out of u and me (assumed) that this would make municipal recycling and composting the same across the province. But when I reached out to people I know in smaller communities, I found that things were much different for them than my experience in the city.

Before getting into their answers, I think it would help to explain how recycling typically works. Here’s a very dumbed-down version: Step 1: Materials are collected. Step 2: Recyclables are transported to a Materials Recovery Facility (MRF—pronounced “merf,” ha!) where they get sorted by material—i.e. glass, metal, cardboard, paper, etc. Recycle BC says there are over 35 MRFS in the province, and from what I can tell, they’re often privately owned. Step 3: Separate materials are sold to different companies who actually recycle things, often overseas. Step 4: The companies that buy used materials transform the materials into new things. Voilà: recycled!

There are many barriers for small communities to enter into the recycling process, like having the funds to provide household pick-up of materials, having a nearby MRF, or having to pay more to send to a far-away MRF. Gas is expensive now, and municipalities are looking to save wherever they can.

Even where recycling is available, it’s not necessarily as encompassing as what I’m used to. For instance, glass is 100% recyclable, but not everyone takes advantage of that fact. In the US, only 33% of glass was reported recycled in 2019, compared to 90% of Swiss and German glass. One way to encourage glass recycling is to have a deposit on bottles. In areas where this happens, 98% of bottles are recycled. But in my motel in Prince George, my glass pasta jar had to go straight into the bin, causing my Environmentalist from Hell’s soul to shudder.

Erin Gibbs is a friend who moved to Nanaimo (population 90,000) a few years ago, and she’s annoyed by the lack of glass recycling in her community. “Glass is not taken by the city or private companies,” Erin wrote me in an email. “So individuals/households tend to either toss it with garbage or collect it for a while and then take it in a batch to the recycling centre.” She mentioned that there is a store in Nanaimo, The Vancouver Island Refillery, that has a take-a-jar-leave-a-jar program.

Glass is 100% recyclable, but in the US, only 33% was reported recycled in 2019.

“So,” Erin wrote, “that’s a good use of glass instead of recycling it after one use. There is an active can-collecting community here, but I think the recycle centres aren’t super central, which means these folks are often going long distances on foot or by bike to cash in their cans.”

My friend Keli, who I quoted above, left Vancouver nearly 8 years ago for a community of about 10,000 people in the Okanagan. She’s been promoting composting for many years and has started her own company, Lekker Land Design, to help people move to a more sustainable way of life. But she feels that her community—which only recently started household compost pick-up—has a long way to go when it comes to living sustainably.

Meanwhile, as mentioned above, my mom’s hometown of Vernon recently switched to a waste collection system where organics are collected weekly, and garbage and recycling are collected every other week. While speaking with a guy in one of my acting classes who lives in the small community of Gibsons—a short ferry ride from Vancouver on the Sunshine Coast—I found out that they also have weekly compost pick-up.

From my informal survey of people I know around BC, it seems like it’s a real hodgepodge system we have going on. If you live in a condo or apartment building, your recycling is done through a private company selected by your strata or building management company. Businesses also differ from residences. With the lack of consistency, it’s understandable why many people and businesses have given up on trying to figure it out.

There are a lot of stressors on people and businesses right now, and I can understand why this isn’t a priority. I reached out to the motel I stayed at for comment, and they never got back to me. Maybe it’s staffing issues, or maybe they just don’t want to get involved in the discussion.

But there are people who are as passionate about this as me. Like Erin in Nanaimo, who brings her recycling and compost home from work where she knows it’ll be properly sorted. If only more people were as indoctrinated about doing this stuff during the 90s as we were!

As a society, we need to get better at reducing and reusing.

Of course, recycling and compost aren’t the only things that matter. When my mom and I spoke about this, she pointed out: “As a society, we need to get better at reducing and reusing.”

She’s right. And things have improved in smaller communities. The reason Vernon now has compost pick-up is because people wanted it, and a pilot program where people dropped off their compost at a few dedicated centres was popular.

“Be the squeaky wheel,” my friend Keli says. “That’s how progress happens… It takes people like you to make the change.” So come on, fellow enviros from Hell. Whether in big cities or small towns, let’s keep squeaking!

Print Issue: Summer/Fall 2022