Flaming out in the Kitchen

We’ve been cooking with fire since the dawn of time, but it’s time to embrace efficient alternatives.

Is an open flame really the be-all and end-all of quality cooking?

With new-normal summer memories of glowing orange skies and pervasive woodsmoke still fresh in our noses, it’s an excellent time to talk about fire. Specifically its use in kitchens, at home and beyond.

Over centuries, we’ve devised all manner of tools and techniques to apply flame to foods — both directly and indirectly — and with good reason. But at this point in time, the idea of burning anything that emits carbon dioxide and pollutants into our shared atmosphere ought to be extinguished, and as quickly as we can manage it.

So should we break up the marriage of flame and food? It’s sure to be a messy divorce, fraught with plenty of conflict and cost. For your consideration, here are the main arguments for and against saving this millennia-old union.

Efficiency

Take the romance of fire out of the equation, and cooking is essentially a question of energy — with efficient transfer being the goal, and waste an increasingly unacceptable by-product.

There are no global statistics on this, but in my experience (as a pro cook and restaurant consultant) about 90% of all cooking with fire is indirect, in that flames heat something — a pot or pan on a range top, air in an oven, or both the air and cooking surface in a wood-fired pizza oven — which then transfers that heat energy to the solid or liquid being cooked. The other 10% includes hot-smoked foods, and those cooked directly by flame-roasting over charcoal or other solid fuel.

Applying the laws of thermodynamics to burgers and fries is the daily specialty at the Food Service Technology Center (FSTC) in San Ramon, CA. An independent testing lab, FSTC evaluates the performance and efficiency of commercial food-service equipment on behalf of both public utilities and their many high-volume customers in the restaurant industry. FSTC test-methods and results also underpin many ENERGY STAR ratings. These have boosted manufacturing standards, and generated incentives for companies and customers seeking energy-efficient options.

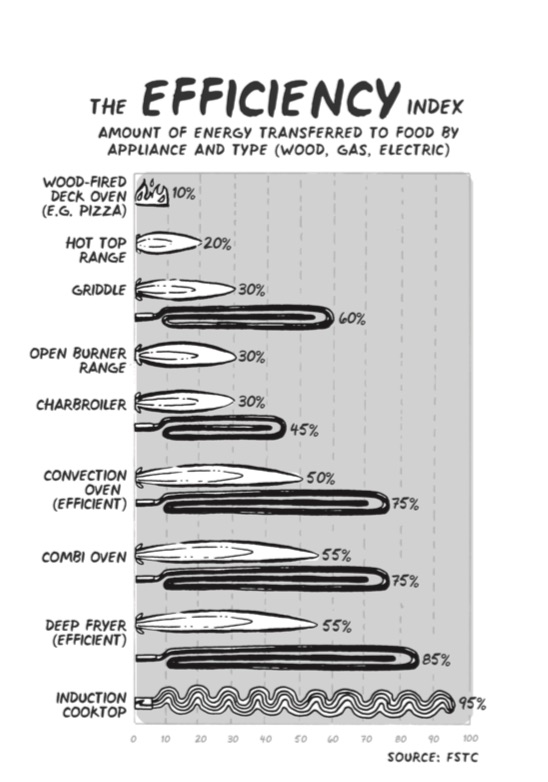

FSTC colleagues and I co-developed this efficiency index for my book about the future of restaurant innovation. It illustrates, from low to high, the cooking efficiency of professional kitchen equipment. As you might expect, wood-fired ovens anchor the low end (max. 10% efficiency), while induction — the best electric technology we currently have — tops the scale at more than 90%.

It’s an uncomfortable realization for waste-conscious chefs that, on average, 70% of the energy put out by their professional gas ranges does no work other than sustaining the kitchen’s can’t-stand-the-heat environment. Given that open gas-burner technology hasn’t improved much in the past 100 years — primarily, I believe, because few chefs have asked — it may never exceed its average 30% efficiency.

We are chefs. If a new and more sustainable way of doing things is what’s needed, we’ll figure out how to cook with it.

However, just as automakers and drivers are counting the internal combustion engine’s numbered days, more equipment manufacturers and professional cooks need to embrace induction. Introduced in the early 1900s, induction’s oscillating magnetic fields efficiently “induce” heat directly in cast-iron and steel (not copper or aluminum) pans. Unlike a gas range or conventional electric element, an induction cooktop hardly radiates any waste heat, so more than 95% of the applied energy can be precisely controlled and directed to most any food. For example, many pastry chefs rely on that accuracy in working with chocolate and other temperature-sensitive products.

Rob Feenie — the award-winning executive chef of Canada’s Cactus Club chain — likes induction cooking’s efficiency enough to install it in his home kitchen, and doesn’t fear a flame-free fate. “Gas happens to be what’s commonly used right now, but it doesn’t have to be part of the future,” he says. “We are chefs. If a new and more sustainable way of doing things is what’s needed, we’ll figure out how to cook with it. We adapt.”

Flavour

Chris Whittaker, former executive chef of Forage and Timber on Vancouver’s Robson Street, plans to specify an all-electric and induction setup for any new kitchen coming his way. “That technology works for my style of cooking, but what about Asian wok cooks who rely on expertly timed blasts of searing heat to create particular flavours?” he says. “Not having an effective equivalent, that’s changing a cuisine.”

Unlike the car analogy — where the type of motor under the hood doesn’t necessarily affect the quality of the driving experience — taking flame entirely out of the cooking equation would impact flavours across global cuisines. If you’ve ever seen a traditional Chinese restaurant kitchen — with its wall of flaming, running-water-cooled woks — you’d be hard-pressed to imagine an electric equivalent. High-powered induction woks are an available alternative, though not without some compromise.

What about Asian wok cooks who rely on expertly timed blasts of searing heat to create particular flavours?

When the City of Vancouver recently proposed restricting natural gas consumption to help its Greenest City 2020 goals, the response from the local restaurant industry was heated. Noted Vancouver chef David Hawksworth makes a case for fire. “Instead of gas, I’d like to burn compressed coconut husks… a renewable, sustainable resource,” he says, inspired by a visit to Kiln in London’s Soho district. “They do all their cooking with this compressed material, and there is fire management, of course, but cooking with flame is the goal. And it works. In London!”

Hawksworth does concur with many of his peers that high-efficiency induction ranges are perfectly suited to many kitchen applications, from boiling water quickly to simmering sauces. Most also agree that ovens, fryers and other appliances — whether electric or gas — are pretty much the same. However, sacrificing the ability to apply flame-generated flavours to certain foods and dishes still seems like a lot to ask…both in the commercial and residential kitchen.

Cost

Given my line of work, I often get asked for recommendations on “the ultimate range” for home kitchens. While I typically make a strong case for an induction range atop an electric convection oven, it’s often impossible to get past the same core challenge faced by pro chefs.

That challenge was evident in a recent Labour Day sale flyer from a major appliance retailer: within a single line of ranges, the stock electric version cost $1,499, the gas model bumped up to $1,999 and the induction option topped out at $2,499. While the induction cooktop can outperform the gas model in terms of speed, efficiency, temperature accuracy, and even safety, it typically comes at a premium price. And if you’re the average non-professional cook committed to reducing your fossil fuel use, you’ll likely need a compelling reason to spend $1,000 more on induction over standard electric.

The price/value gap gets even wider in the professional realm. Standard gas ranges are generally inexpensive, especially in the pre-owned market (where few induction ranges are found, and many start-up restaurants buy their gear). While volume deals can be had, the average price on a comparably equipped new induction range is typically 100–150% more than the natural-gas version. Furthermore, to match the power and reliability (if not efficiency) of gas equipment, commercial-grade induction ranges need 3000W-5000W elements — up to 8000W for induction wok stations — which can be a problem unto itself.

Induction is fast, clean, efficient… but we still need something better.

Chef-owner Andrea Carlson found out just how power-hungry induction can be when she was sorting out her kitchen at Vancouver’s Burdock & Co: “The utility told us our building wasn’t wired in a way that allowed us to install as much induction as we wanted [at a reasonable cost],” she says. “Induction is fast, clean, efficient… but we still need something better.”

In the predominantly bottom-line driven restaurant business, monthly energy costs for induction ranges can be 75–100% more than their gas-powered equivalents, even in BC where electricity is inexpensive. Winnipeg-based freelance chef/caterer Ben Kramer would like to see better and leaner induction: “It’s efficient and precise, but not cheap to buy or use. And, as with many energy-efficient solutions — like heat pumps and solar panels — in order to save $3,000 over 5 years, I have to spend $20,000. If they want to encourage a fuel switch from gas, the electric utilities and city governments will need to offer some very healthy incentives.” Given the rapidly evolving changes to every other cost of urban living, the investment needed to flip that switch is unlikely to be a priority in most city halls or kitchens.

To summarize, the cases for and against cooking with fire include issues of inefficiency and waste versus authentic flavours and tradition, laid over business-as-usual economics. In the absence of some other disruptive element, the prospect of a win-win resolution is still on the back burner.

Vancouver celebrity-chef/restaurateur Vikram Vij is optimistic by nature, and fully expects a high-efficiency, low-cost cooking technology will someday allow the sustainability of his kitchen to match that of a local organic menu. “I think we ought to have solar panels on rooftops to energize our kitchens, and technologies to recover heat from water and air and redirect it to growing produce,” says Vij. “It may take another Elon Musk, though, to build the next-generation range that has zero-waste heat and energy.”