Zero-Waste Grocers Take Shopping Back to the Future

Vancouver’s Nada grocery eliminates waste by combining old-time shopping methods and up-to-the minute tech.

Varied containers of dry goods await zero-waste shoppers at a pop-up prior to the opening of their brick-and-mortar store.

Each year, metro Vancouver residents throw out enough garbage to fill the local football stadium almost twice; that’s nearly 700,000 metric tonnes packed into landfills annually. The region has launched initiatives to reduce this figure, but fundamental problems still need to be addressed, including the way we shop for food. This is where Brianne Miller and Alison Carr come in: as grocers, they’re working to reconcile their industry’s past, present, and future in a bid to bring about serious waste reduction.

Miller and Carr are the co-owners of Nada, a zero-waste grocery store set to open this spring in Vancouver. Their business began in 2015 as Zero Waste Market, a pop-up shop first held regularly at the local Patagonia store. Since December, they’ve been hosting pop-ups in the brick and mortar location on East Broadway that will be Nada’s permanent home once renovations are complete (they received their building permits at the beginning of February). With their new space, they feel they are “definitely participating in a worldwide movement of grocery stores,” says Carr, with local examples like The Soap Dispensary to draw on for inspiration. (Models further afield include Germany’s Original Unverpackt, France’s Day By Day chain, Ottawa’s NU Grocery, and Denver’s Zero Market.)

Nada’s format will be unique to Vancouver in many ways, though. For both their pop-ups and store, Miller and Carr’s concept is simple: instead of buying food off the shelf in single-use packages, customers bring in their own bags and containers (or purchase reusable carriers from brands like Onyx on site). Shoppers’ containers are weighed before being filled from larger bulk bins. That weight is then deducted from the overall cost, and customers walk away with as much or as little of the product as they need. This reduces both food waste and the amount of packaging headed to the landfill.

Brianne Miller and Alison Carr want Nada to be an example of better business practices in the grocery industry.

Waste-reduction has not historically been the focus of grocery industry innovation. For the most part, companies have sought to increase efficiency and find alternative ways of shopping, like online ordering and home delivery. There is movement toward reducing food waste within stores, a problem connected to overstocked product displays, expiration dates, and the expectation of perfect-looking fruit and vegetables. Considering that $31 billion worth of food is wasted every year in Canada alone — around 40% of the food produced annually in the country — there is still a long way to go.

With Nada, Miller and Carr are looking to address these issues by building a new kind of system, and be an example of what Carr says a “grocery store practicing better business practices can look like.” That requires some innovative thinking, and the past is a good place to start. In reimagining the future of grocery shopping, they’re drawing on both twentieth and twenty-first century models for inspiration.

While the way we buy food has evolved over the decades, the most impactful shift took place early in the twentieth century. Before 1915, shopping fit the butcher-baker-candlestick-maker mold, with people visiting different stores for different products. Most shops were operated by clerks standing behind a counter, serving customers one at a time. At dry goods shops, clerks portioned out food into reusable containers from bulk bins, giving customers the amount they requested. It wasn’t efficient, though, and lines could get long.

In 1916, the opening of Memphis, Tennessee’s Piggly Wiggly store signalled change. Rather than having a large number of clerks portioning out products, the store instead asked customers to pick up baskets, wander through aisles, and personally select the food they wanted off shelves. While this both increased efficiency and shoppers’ sense of autonomy, it also required that food be sold in individually packaged containers of standardized portions.

While Piggly Wiggly ushered in the era of self-service, it wasn’t until the 1950s that the concept of the modern supermarket became fully entrenched. Stores were bright, product displays were elaborate, and packaging became a powerful way to advertise products. Cellophane became popular for its ability to protect food while allowing shoppers to see what they were buying. Conveniently packaged food had truly arrived.

In creating Nada, Miller and Carr don’t wish to return to the pre-Piggly-Wiggly past, but they do want to create a system that takes the best of both older and modern grocery styles.

First, Carr says, they’re “trying to utilize tech, especially in [a] city where it’s so prominent,” and develop new tools that create an efficient but waste-conscious store. The self-service model will persist, but it won’t consist of reaching for a package from the shelf. Nada will have custom-designed scales that allow customers to weigh their own containers before filling them. This will go for all types of groceries, not just the ones traditionally found in a bulk aisle. Nada is “looking [to create] a system where it makes refilling easier, quicker, more efficient, and more streamlined,” says Carr.

Nada will also have a snack bar, and with it Carr says they hope to “close the loop… [by] offering smoothies and snacks that use imperfect ingredients from the store.”

With the exception of a meat department — the logistics of which still need to be sorted out — Nada will carry the same products a traditional grocery store would, setting it apart from the majority of zero-waste stores already in existence. This include items package-free shops tend to avoid due to shorter expiration periods, like fresh hummus and pasta sauce. Across the store, products will be mindfully sourced, with everything from organic and fair-trade standards, to local production and labour ethics in mind. They’ll arrive in bulk from suppliers, with an emphasis on reusable packaging at every point in the chain.

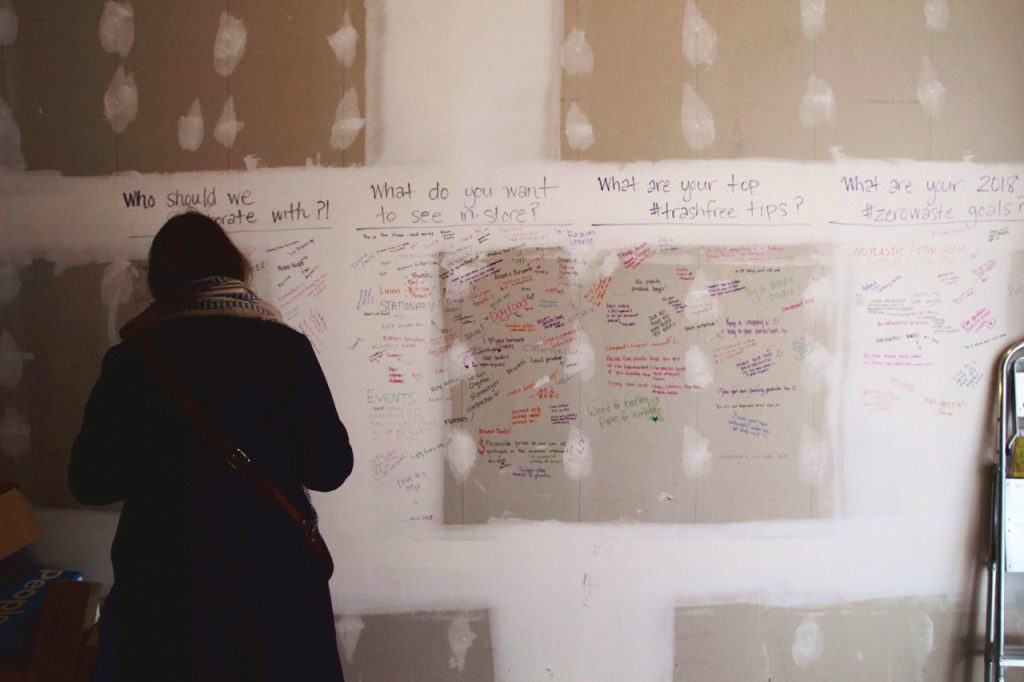

Nada cultivates community at a January 2018 pop-up in their future home, by inviting shoppers to share suggestions on the store’s unpainted walls.

Miller and Carr are innovating in another realm as well: they hope to cultivate a sense of community surrounding Nada, not a common supermarket goal. They plan to host film screenings and workshops, with topics like reducing kitchen waste and using food scraps in cooking. Miller and Carr’s community-based philosophy has served them well so far: their crowdfunding campaign to cover startup costs raised $55,555, more than twice their initial goal.

Nada’s owners are aware that the waste-conscious lifestyle can be cost-prohibitive. Prominent zero-waste blogger Béa Johnson, for example, is a white, upper-class woman living in a sleek California home. Her lifestyle, and the time she dedicates to her zero-waste habits, are out of reach for most people. Miller and Carr want to lower the barriers to zero-waste living. Says Carr, “We’re really trying to keep this movement in our city as accessible and inviting as possible.”