Can Inclusive Cycling Culture Be Brewed in a Coffee Pot?

Coffee Outside gatherings and “no-drop” group rides offer alternatives to competitive cycling.

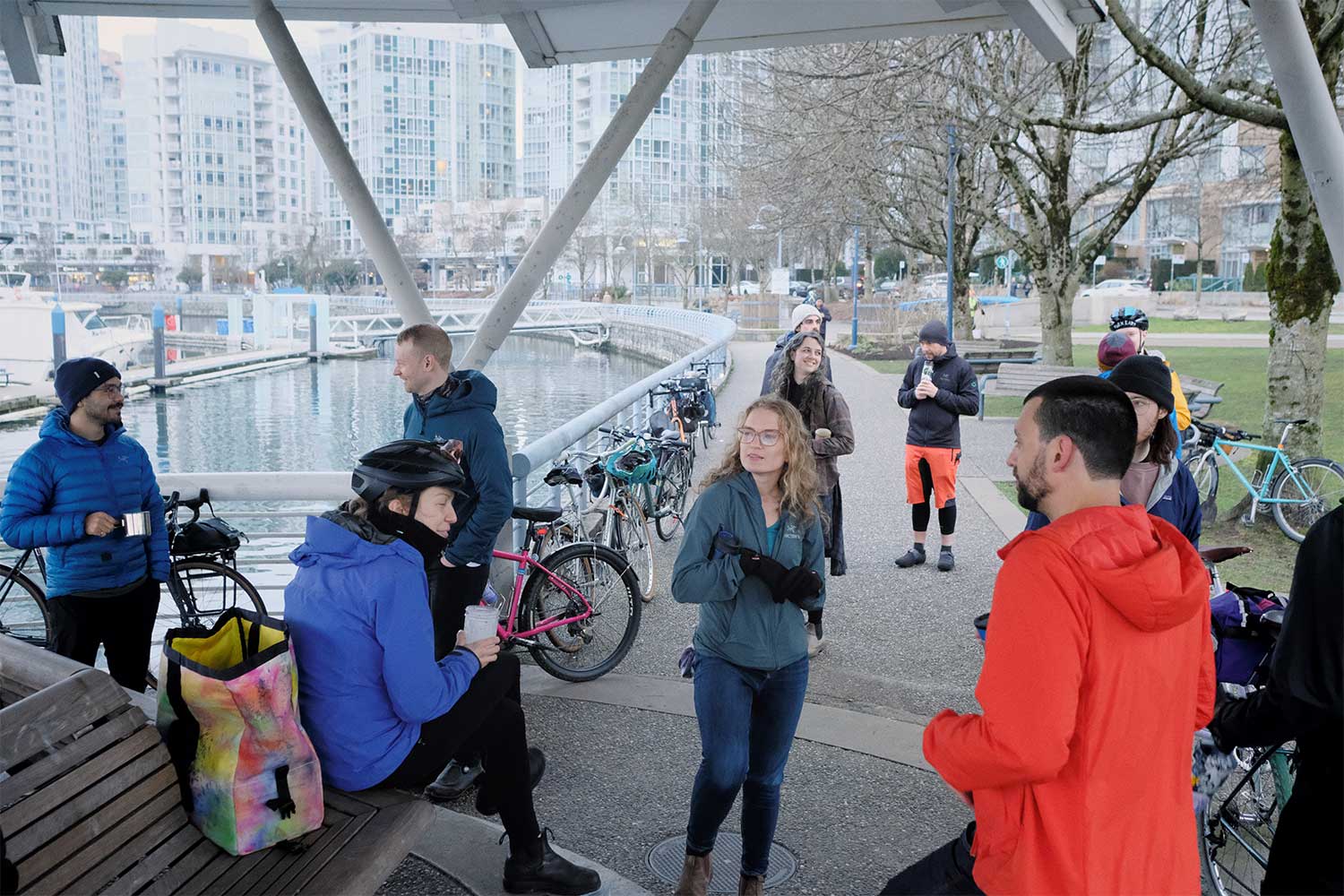

It’s early, but that hasn’t stopped these cyclists from meeting to brew coffee and chat at Vancouver’s Coffee Outside.

The sun has just risen, and it’s cold enough to see your breath. It’s 7 am, and downtown Vancouver is still approaching peak bustle. At a park in the ritzy neighbourhood of Yaletown, a small group of cyclists are meeting for the first time in months, thanks to a recent loosening of pandemic restrictions.

They’re scattered around in clusters of three to five, chatting, their bikes propped up against railings or nearby trees. In the middle of the group, someone brews a fresh cup of coffee on a tiny camping stove.

This weekly scene repeats itself in cities around the world. Across five continents, groups of cycle-minded people meet early in the morning, once a week, to enjoy a brew in the fresh air. They call it Coffee Outside. Non-competitive cycling gatherings like this provide refreshing alternatives to the wider sport’s culture of competition and elitism.

Community over competition

Russ Roca — a cycling-focused YouTuber based in Missoula, MT — says his interest in Coffee Outside is an extension of his love for non-competitive cycling. He helped popularize the idea of the gatherings through his YouTube channel and website, The Path Less Pedaled.

“I came to cycling from a completely different path [than competition],” Roca says. “For me, my truck died, and I needed a way to get around.” He was working as a photographer at the time, and instead of fixing the truck, he replaced it with a bike. He began transporting his gear with pedal power alone, marketing himself as the eco-friendly Bicycling Photographer.

Roca’s friend Rob Perks owns Ocean Air Cycles in Ventura, CA, and is the self-proclaimed originator of the hashtag #CoffeeOutside (some time around 2013). But Roca first attended Coffee Outside in Portland, OR, where he used to live. His video of that gathering, which shows cyclists of varying ages by a misty lake, “made the concept click for lots of people,” he says.

We’d see people that didn’t identify as a cyclist and invite them, to show there’s a community they could participate in.

Eventually, cycling became the focal point of Roca’s career, but he never connected with the hard-and-fast riding style that he feels dominates cycling culture. “In some ways, I look at competitive cycling as like competitive eating. [Unfortunately] it’s about… how fast you can do it, and any other joys that it might bring are thrown out the window.”

Coffee Outside, on the other hand, isn’t about going fast. Gatherings have popped up in cities as far off as Moscow, Hanover (Germany), Minsk, Sacramento, and Montréal. The Path Less Pedaled website has a Coffee Outside map to help people find their own local gatherings.

Cycling events that offer connection to community instead of competition appeal to a wider range of people, Roca says. “You didn’t have to be a bike nerd to get involved,” he says about the first gatherings he attended. “We’d see people that did not own a very expensive bike, people that didn’t identify as a cyclist, but we’d invite them to show that there’s this community they could participate [in].”

Bringing camping to the city

The “simplicity of community” is what Morgan Taylor says was missing before they and their partner Stephanie (also Taylor) started the Vancouver chapter of Coffee Outside in 2017.

Taylor, an elementary school teacher and cycling journalist, says that starting the local group — known by its social media handle @CoffeeOutsideYVR — was a welcome change to how they interacted with cycling culture. “I’ve been writing about bikes professionally for a decade. Writing about it is one side, but the community side is really what I connected with.”

Taylor was inspired to start their own gatherings after meeting Perks. Morgan and Stephanie briefly stayed with him in California during a three-month-long cycle-camping trip down the west coast of North America.

“If we could go camping all the time, it’d be wonderful,” they say. “But you can’t. It’s not really a viable career to be a professional bicycle camper!” The gatherings have brought the cozy feeling of camping to their regular work weeks, without the prep, commitment, and travel of actual camping.

Community formed around Coffee Outside in Vancouver quite quickly, says Taylor, who is reluctant to take credit for organizing the gatherings. “While I still run the Instagram account, I feel like the gathering, even very early on, became a community thing.”

Building a welcoming space

Being inclusive to people regardless of whether they’re interested in the finer points of bicycle mechanics is important for Taylor. When they started doing social rides with the community that formed around Coffee Outside — a common activity within different Coffee Outside chapters — they made a point of talking to the group in advance of the rides and asking them to find anything but bikes to talk about. “As bike enthusiasts, we can really get stuck in that, [but] it’s the experience that the bikes enable that I think is the real magic.”

The @CoffeeOutsideYVR Instagram account now has more than 2,000 followers. Taylor has used the platform to organize fundraisers for Our Community Bikes, a Vancouver-based shop that teaches people how to fix their own cycles. It also provides bicycles to low-income individuals, and provides a safer space for groups who haven’t historically been welcomed by the cycling world. “They have been creating space for people who are not invited into bike shops,” Taylor says.

As bike enthusiasts, we can get stuck talking about bikes. But the experience they enable is the real magic.

Even so, Taylor sees a lot of work left to do if cycling communities are to be truly inclusive. “I look at the group that does show up [to Coffee Outside]. Most of them have a bike that’s not cheap, and primarily they’re white.” They point to the fact that it can still be difficult to join the community when you have no one to go with, as well as larger systemic obstacles like wealth disparities and racism. “I’m recognizing that we do have gaps in our ‘inclusivity,’” Taylor reflects.

Making group rides inclusive

Cory Hadley had been working at a bike shop in Vancouver when she started attending mainstream group rides, and she too noticed a lack of inclusion. “There wasn’t really any ride out there that was slowly paced, all bikes welcome,” she said. “I found that you needed to ride fast, have a flashy carbon bike, and wear spandex.”

She also noticed gender disparities on the rides. “Cycling is a very male, cis[gender]-dominated sport,” Hadley says.

The gender gap in cycling is well documented: non-male participation in both sport and non-sport cycling are comparatively low. For instance, Statistics Canada reported in 2017 that 46% of males had cycled in the past year, compared to 34% of females, “regardless of age, income, or education.” Researchers say that cultural factors, like expectations for workplace appearance and likelihood to have children in tow, may contribute to the gender gap in cycling as transportation. Risk-aversion might also contribute to the gender gap, with significantly more women than men feeling constrained by potential traffic and aggression from drivers.

To challenge these norms, Hadley started Chill Rides Vancouver in 2019: a beginner-friendly “safe and inclusive space for women, non-binary, and queer cyclists.”

No one gets left behind, which makes for a more accessible experience — especially for new cyclists.

Her small idea also revealed an unaddressed appetite for more inclusive rides in the city. Quickly, she had to enlist volunteer cyclists to head up the front and back, to help keep the group moving at an even pace.

These pace-keepers are part of what ensures Chill Rides’ “no-drop” policy. In conventional group rides, Hadley says, there’s no waiting for slower riders, which she sees as dangerous. “What happens if you go [to] a completely new area and you get dropped, and you’re stuck? What happens if you get a flat, or your phone dies? That happened to me.” But no one gets left behind at Chill Rides, says Hadley, which makes for a more accessible and easygoing experience, especially for new cyclists.

Hadley says that Chill Rides is only going to get bigger. “More people are looking for ways to get around the city [without] a car or the bus.”

Meanwhile, Roca from Path Less Pedaled says he’s noticing that big racing-focused brands are starting to pay attention to the growing success of Coffee Outside. Rapha, an elite cycling gear company, posted to social media last year about making coffee while out cycling. “It’s kind of been funny to see,” he says. “Years later, these über competitive brands being like ‘We’re cool too!’”

For Taylor, Coffee Outside has given them pause to reflect on their role in the small community that has formed around the gatherings, and to be grateful for those who continue to show up.

“Just being able to have a gathering is a pretty big deal,” they say. “The two of us started the thing, but the leadership of the group formed naturally because people kept showing up. And if you keep showing up, then you have a voice.”