Buy-Nothing Parenting

How to find a way out of consumer kid culture without losing your mind.

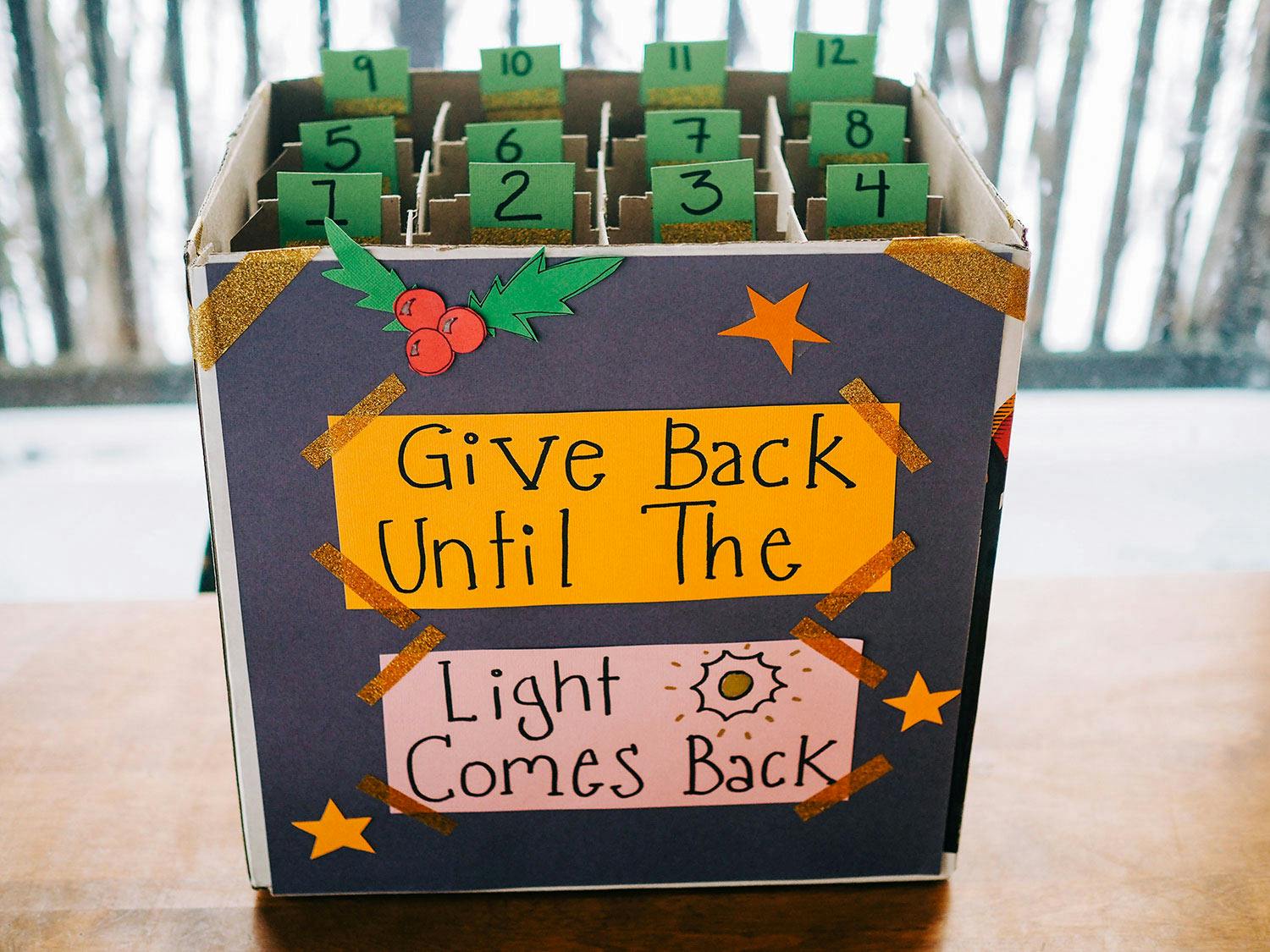

This year, we’re trying out a reverse advent calendar. Instead of the kids opening a door and getting a chocolate each day, we’ll find a new way to give back to the community together.

I was at a playgroup just before Halloween, casually eavesdropping on some moms talking about buying costumes. “I just couldn’t believe what the Aurora costume cost me at the Disney Store: 80 bucks!” one said. Another spent even more on an adult Daffy Duck costume so she’d match her daughter.

I thought about joining in, but what would I say? “Oh, tell me about it! I had to pay a whopping $8 for my 4-year-old son’s Elsa costume on VarageSale!” Confident that wouldn’t make me any friends, I pragmatically chose silence.

Most of my family’s possessions, from puzzles to furniture, were acquired through swapping, bartering, thrifting, or inheriting. If I really can’t find it second-hand, I buy online to avoid splurging on things we don’t need. You won’t find many brand-name goods in our house, though we rarely say no if we’re given something useful-but-branded. (That said, gender-binary-and-unrealistic-body-enforcing franchises like Barbie are a no-go for me.) The kids don’t look like they came out of a catalog, but they don’t seem to mind.

Modern parenting is so closely tied to consumerism, I’m tempted to return to my short-lived anarchist phase.

Parents are a marketer’s dream: we’re tired, short on time, and want “the best” for our kids. At some point, we were sold the idea that having a great family life meant buying stuff. On any given Saturday, my local Walmart is 1,000-times busier than our river trail system. I get it; so many of us are strapped for cash, but it takes time and mental space to find quality used goods. Modern parenting is so closely tied to consumerism, I’m tempted to return to my short-lived anarchist phase. Instead, I remind myself good parents don’t have to be good capitalists.

There’s more than one bottom line

Like so many North American families, our budget gets eaten up by childcare, mortgage payments, and groceries. The average Canadian carries C$23,000 in non-mortgage debt, according to the Credit Counselling Society. In light of how easy it is to slide into the red, I try to cut every corner I can.

Finances are an incentive to live lighter, but planetary and human costs loom larger for me. Between their greenhouse gas emissions, water pollution, and exploitative labour practices, I’m just not keen on the textile and toy industries. I know my individual actions are a drop in the bucket, but doing nothing while the planet burns doesn’t feel like an option.

My family bonds through activities that don’t involve purchasing stuff.

In a 2018 literature review on how materialism develops in children, researcher Marsha Richins emphasizes the importance of parents helping kids develop a sense of identity beyond their things. My family bonds through activities that don’t involve purchasing stuff. When the kids ask for toys, our typical answer is “we’re choosing to spend our money in other ways.” Then we go to the pool, put on our cross-country skis, or take out a game from the library.

Ditch “tie-in” television

Unless you live on a sailboat or in the wilderness (both very appealing), it’s not easy to resist the commodification of childhood. Some days I feel like Disney characters lurk in every corner, while Paw Patrol hides in plain sight.

Research shows that kids who consume more TV with targeted ads have higher rates of materialism. The Canadian Pediatric Society recommends choosing non-commercial television sources, and avoiding ads when possible. For a time, I tried to parent totally screen-free while working from home with two kids under five. It was disastrous for my mental health.

I still try to regulate what my kids watch; they’re usually happy with streamed episodes of Magic School Bus and blurry re-runs of Today’s Special. Although I’d enjoy Miss Frizzle or Muffy Mouse toys, I appreciate these shows’ lack of large-scale merchandise tie-ins.

Secondhand clothes can be first-class fun

The average Canadian household spent C$3,430 on clothing in 2017, according to Statistics Canada — just a few hundred less than on recreation. I’m thrilled we don’t spend anywhere near that. But the fact 90% of our clothing is secondhand is a sign of our privilege: thrifting takes time, scanning online sites requires technology and time, and my hand-me-downs come from a community lucky enough to have clothes to pass along.

My kids are young, but I’m already stockpiling ideas for the future. Sarah Elmeligi of Canmore, Alberta, told me she only buys secondhand clothes for her two teens. For Christmas, Elmeligi asked her 14-year-old what she wanted, and her list specified only used clothing. When asked why, the teen mentioned the clothing industry’s pollution and abuse of workers, and pointed out that “used clothes are so much more unique. I’m curious to see what people find for me!”

When we get a box of hand-me-downs, we look through it as enthusiastically as we would store aisles — trying things on, putting on fashion shows, and assembling outfits.

By framing consignment clothing as an expression of creativity, I hope to foster this same attitude in my kids. When we get a box of hand-me-downs, we look through it as enthusiastically as we would store aisles — trying things on, putting on fashion shows, and assembling outfits.

As writer Jillian Johnsrud pointed out in a 2016 blog entry, “Shaped by Poverty,” buying secondhand can be hard for those raised with less. “I still struggle walking into a thrift store, there is something about the familiar smell of used clothing that makes me feel uneasy,” she wrote. “We don’t want to look poor.” As someone who can afford to shop at the swankier consignment stores, I know I’m lucky not to be saddled with those associations.

Out with the old, in with the new (to you)

I really like what Tracy Keats-LaPointe of Calgary does with her kindergarten-aged son. If he wants something new, “he will make a ‘sell’ pile from his current toys so that he can afford to buy it, and also make space for it in our minimalist toy collection.” They sell on Facebook Marketplace or to local consignment stores, and rarely buy anything actually new.

I’ve personally had great luck on Varagesale, a local-to-your-community buy-and-sell app that’s a bit less anonymous than similar services, because participants need to sign in with Facebook accounts. The Buy Nothing Project has local Facebook-based groups that let communities create what they call a “gift economy.” (A box of baby blankets is currently on my porch waiting for a young single mother to pick it up, in fact!) While we don’t yet have one in my town, toy libraries are popping up globally for parents who either can’t afford — or don’t want to buy — piles of new things to spice up their toybox.

In the lead up to this Winter Solstice, my family is going to try out a reverse advent calendar. Instead of the kids opening a door and getting a chocolate each day, we’ll find a new way to give back to the community together. If all goes according to plan, we’ll give winter gear to a homeless shelter, carol in our neighbourhood, and bake cookies for a seniors’ residence.

The laughter those moms shared over costume-buying reminded me that parenting culture not only encourages consumerism, we often don’t know how to connect without it. In retrospect, I wish I’d found a way to join their conversation. Whether you’re buying used or refusing to buy, these choices need to be normalized. Not just for our pocketbooks, but for the planet, and the little people who will inherit it.

Print Issue: Winter/Spring 2020

Print Title: Buy-Nothing Parenting