The Wet’suwet’en Aren’t Just Protecting “the Environment”

The Unist’ot’en and Gidimt’en land defenders aren’t just fighting pipelines, they’re fighting for a way of life.

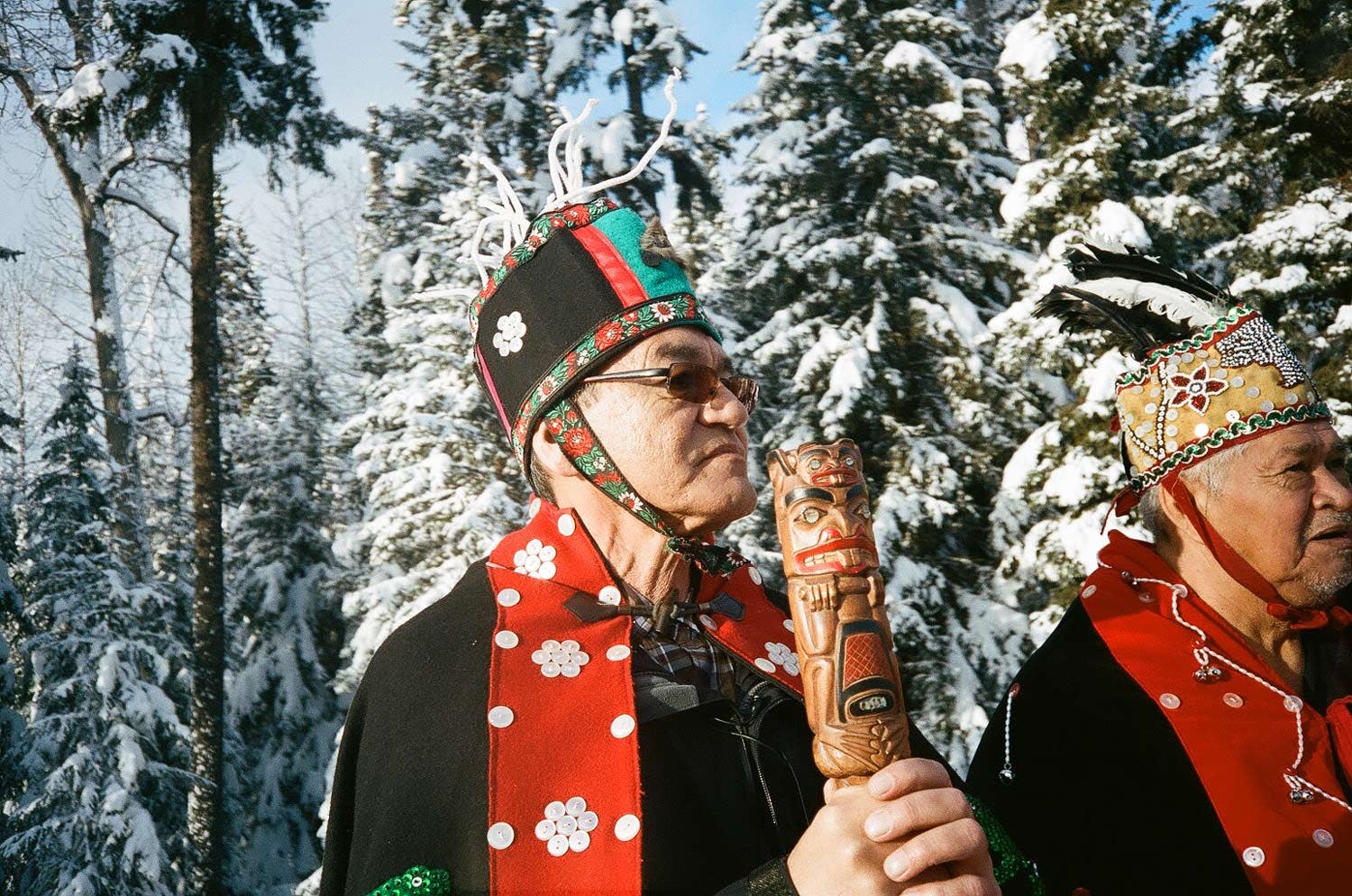

The Hereditary Chiefs are the voices of their clans. Collectively they represent the voices of the Wet’suwet’en people.

I am a Tlingit land defender, an anti-colonial organizer and scholar, and a neighbour to the Wet’suwet’en people. I do not speak on their behalf, but as a supporter who has been returning to Unist’ot’en Village to help build their land-based Healing Centre and traditional territory re-occupation since 2015. I have been on site full-time since December 2018.

We wake up early, pull clothes over our winter underlayers. Gather in the dining hall of the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre as dawn breaks. We hear there are police amassing in Houston, the nearest town, that they are headed up the logging road toward us. They will have to pass through the Gidimt’en access point 22 kilometres away to reach us here, at Unist’ot’en. None of us have slept more than a handful of hours in as many days. We put more coffee on. I make eye contact with the other Indigenous people gathered. We offer each other medicine — sage and cedar and devil’s club. Smile at each other. We are under siege, but we are not afraid.

On January 7, 2019, militarized police raided an Indigenous camp in northern so-called British Columbia, Canada. The sniper rifles, tactical gear, and unsubtle threat of lethal force deployed against unarmed Gidimt’en clan members and allies at the access point garnered international attention and support for the Indigenous re-occupation of traditional Wet’suwet’en lands. The raid was a violent enforcement of an injunction order granted to the Coastal GasLink pipeline company (CGL), and was meant to remove obstructions to pipeline construction on the territory of the Unist’ot’en house group, part of the C’ihlts’ehkhyu clan of the Wet’suwet’en nation.

CGL has courted band councils along the pipeline route, soliciting “approval” for the pipeline from these governments that were imposed by colonizers to undermine traditional Indigenous systems. On Wet’suwet’en territory, the company has encountered a robust and powerful hereditary governance structure that has been in practice for thousands of years before colonial occupation, before Canada was founded.

The raid demonstrated the lengths to which Canada will go to protect industry’s interests on lands over which they have no legitimate jurisdiction. Fourteen people were arrested for civil contempt as they upheld Wet’suwet’en law and protected the territory from invasion. On April 15, 2019, all contempt charges were dropped by the court.

We are enraged, and sad, and not surprised. We have faced this colonial violence before.

We hear that the gate at the Gidimt’en access point has been breached. See snippets of footage on media. There have been arrests, and injuries. Later, a small group of our friends arrive, having fled the police violence. We expect the police to be right behind them, ready to raid Unist’ot’en Village next. We watch footage of the raid, hear the matriarchs singing the “Women’s Warrior Song,” see our relatives standing powerful and calm in the face of extreme force.

A tactical officer climbs over the reinforced gate, his assault rifle waving recklessly in the faces of the Indigenous people on the front line. We are enraged, and sad, and not surprised. We have faced this colonial violence before, we see the same old patterns behind new faces. We watch, and wait for the wave of police to arrive at our door.

Unist’ot’en Village is not a protest camp. For the past ten years, Freda Huson and her family have re-occupied their house group’s traditional territory, Talbits Kwah, along the Wedzin Kwah (Morice River). With the help of supporters from around the world, Freda built a cabin, a bunkhouse, a traditional pithouse, a permaculture garden, and operated a checkpoint to control access to the territory. They built a Healing Centre where Wet’suwet’en people can return to the land to find healing from colonial trauma and addiction, and have begun to offer programs to fulfil the long-term vision of healing Indigenous people.

Unist’ot’en have re-built connections to their land and ancestors by hunting, trapping, gathering medicines, berry picking, and living in the path of numerous proposed pipelines. Unist’ot’en Village is a home, a space of healing and regeneration, a place where Wet’suwet’en people and supporters have built community in the spirit of Indigenous resistance.

Talbits Kwah holds the stories of Unist’ot’en people. The land holds the ancestors, the ancestors are present in the struggle. They are present in Freda when she speaks about her grandmother’s call to protect the land. They fight alongside us as we stand with our Wet’suwet’en relatives. They have defeated several pipelines already (including the Enbridge Northern Gateway oil pipeline), and this one will be no different. Coastal GasLink is no match for the power of the land, the river, the animals, the ancestors, the people.

Unist’ot’en Village is not a protest camp. It’s a home, a space of healing and regeneration.

News starts to trickle in about solidarity actions around the world. Thousands of people in the streets of Toronto. The port of Vancouver shut down. People following Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, drumming and singing, shutting down his events, and calling him to account for RCMP actions on the territory of the Gidimt’en clan. We are still expecting police to arrive here, but they never come.

Instead, the Hereditary Chiefs arrive, and tell us that they have decided to comply with the injunction to avoid bringing violence and harm to the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre, which is home to several clients of the healing program. Two days later, CGL arrives under RCMP escort to dismantle the gate and begin clearing the road behind the Unist’ot’en checkpoint. Using the injunction as a weapon and the threat of lethal violence, they force their way onto unceded Unist’ot’en territory.

The Wet’suwet’en people have been living their system of governance for thousands of years. The system is enacted through the feast hall, where members of each of the five clans gather, where the Hereditary Chiefs of the clans speak and sit and eat, where conflicts are resolved, debts paid, and decisions made.

In the feast hall over the past eight years, the high Hereditary Chiefs of the five Wet’suwet’en clans have opposed the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline. In the feast hall on December 15, 2018, the Gidimt’en clan announced it would set up an access point, and all the other clans spoke in support.

The Hereditary Chiefs are the voices of their clans, collectively they represent the voices of the Wet’suwet’en people. The names they carry, passed down for millennia, correspond directly to particular territories, for which they are responsible. Protecting the land is the foundation of Wet’suwet’en law.

Coastal GasLink is no match for the power of the land, the river, the animals, the ancestors, the people.

Seeking consent to access and pass through and harvest from neighbouring clans’ territories is the foundation of Wet’suwet’en governance. At the root of the dispute with CGL is a fundamental disrespect for Indigenous land and people, as exemplified by the company’s dismissal of the Hereditary Chiefs’ right to say “no.”

There can be no pipelines on Wet’suwet’en territory without consent. The injunction and its enforcement literally trample over Wet’suwet’en people and territories, ignoring consent and forcing compliance with a legal order that aims to replace Indigenous law and governance. The injunction ignores Canadian law as well, discarding the results of the Delgamuukw/Gisday’wa Supreme Court case, which determined that Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan peoples’ Aboriginal title had never been extinguished. Their lands were never ceded or surrendered to the Crown.

The company insists that activities at the Healing Centre can go on uninterrupted, while they travel daily past Unist’ot’en Village to do their pre-construction work and to clear space for their proposed “man camp.” In the back of the territory, 20 kilometres from the Unist’ot’en checkpoint, the hum of generators and the movement of machines can be heard from the sweat lodge and the trappers’ cabin. They designate huge areas on the territory as “construction sites,” and deny access to Unist’ot’en people and supporters.

RCMP begin patrolling the road several times a day, stopping Unist’ot’en supporters and Healing Centre residents to harass us, ask us for identification, and film our activities. We conduct ceremonies on the land and are threatened with arrest. We try to check our traplines and are threatened with arrest. Our trapping season is ruined. We don’t even think about trying to hunt for beavers as the ice breaks up in the spring. We are blocked from accessing parts of the territory, blocked from ceremony, blocked from the land, blocked from our relatives.

CGL’s security personnel and site managers read us the injunction notice again, and again, and again. It becomes a refrain that punctuates our dispossession. We watch the invasion of the territory, daily. When keen white environmentalists and anarchists arrive to support the camp, we are tired and run down from the daily harassment and disrespect. “There must be something that can be done to stop CGL,” they tell us. They don’t understand how the chiefs could “let this happen.” They are angry and restless, and they burn out almost immediately.

I make eye contact with the other Indigenous people gathered. We offer each other medicine — sage and cedar and devil’s club. We have been fighting the colonizers for hundreds of years. We will keep fighting. “This isn’t over,” Freda tells us, “I’m not defeated. This isn’t over.”

We are not protecting “the environment.” We are helping our relatives survive, just like they help us to survive.

Fundamentally, the position of the Unist’ot’en people is about defending their right to live free on their unceded territories. It is about protecting the land so that future generations of Wet’suwet’en people can do the same. It is about creating a space of healing, and re-connecting Indigenous people to the land and our other-than-human relations. It is about re-establishing our responsibilities to live in good relation to the land, and animals, and water.

It is about strengthening our collective ability to survive, and thrive, in balance with the “natural world,” which does not exist separate from us. For these reasons, characterizations of the Wet’suwet’en struggle as an “environmental” conflict are false. They fail to account for the interconnection between our Indigenous communities and the non-human communities we care for.

We are not protecting “the environment.” We are helping our relatives survive, just like they help us to survive. We are also not saving “the environment” for white settlers to enjoy or consume. What Unist’ot’en Village does do is to embody an alternative way of living, a way of re-orienting our lives to repair our connections to the world beyond human relations, a more socially and ecologically sustainable way of being.

Participating in this alternative is a gift that Unist’ot’en matriarchs have offered to supporters, and it is a model that has inspired other Indigenous grassroots movements for nearly a decade. It is a form of organizing that is firmly rooted in Indigenous relationships to land and place, that starts with the demand to live unimpeded and uncontaminated lives on our autonomous territories.

We drive to the back of the territory to check the trapline. Learning how to trap has been a joy and a privilege for me as a Tlingit guest on Wet’suwet’en territory. I am always grateful for learning cultural practices on this land, for the ancestors who took care of the territory and passed along their care to the generation leading the fight now. Today, I am excited to walk the trapline with my Gitxsan and Tahltan neighbours. All of us are here to support the Wet’suwet’en, our traditional allies and trading partners, and sometime-enemies.

But today, we are stopped on the road by CGL employees. They read us the injunction. They call the police. “Ever since you first came here,” my Gitxsan friend tells them, “you’ve been criminalizing the way we live.” They blockade the road, using the threat of arrest to claim control over access to the territory. We are not allowed to check the trapline. We are not allowed to conduct our ceremonies. We are not allowed to live. We are not supposed to survive, to thrive, to resist.

The injunction is part of a colonial toolkit meant to expedite industrial projects by criminalizing Indigenous dissent. The police are deployed to accompany contractors and company employees in order to ensure that work can “safely” proceed without the consent of the Hereditary Chiefs. There is no right to say “no.”

In every case, the desires of the company to conduct work as quickly as possible are held up over fundamental Indigenous rights to hunt, trap, gather, and simply exist on Indigenous lands. Our way of life is criminalized. The right of the Unist’ot’en people to control access to and use of their territory — enshrined in both the Canadian constitution under Aboriginal title and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous people — is wrested from their grasp by a gas company using Canadian law as a weapon, using police as private security, using the threat of jail, using the threat of violence.

The right of the Unist’ot’en people to control access to and use of their territory is wrested from their grasp by a gas company using Canadian law as a weapon, using police as private security.

We feel this criminalization acutely — it is a continuation of a colonial pattern that has been used against our peoples since contact. Our spiritual and cultural practices have been outlawed and punished. Singing and drumming and speaking our languages landed our ancestors in jail. In the case of Northwest Coastal peoples, the potlatch was banned for a hundred years, effectively criminalizing the practice of Indigenous law and governance.

In this context, enforcing the injunction over and above Wet’suwet’en law and Indigenous title and rights is an act of colonial subterfuge. Wet’suwet’en law is not less legitimate than Canadian law, especially given that the lands in question were never ceded or surrendered to the Crown. Trespass and occupation without consent is illegal under both Indigenous and Canadian legal precedents. The system of hereditary governance that is practiced in the Wet’suwet’en feast hall has effectively protected and managed Wet’suwet’en lands for thousands of years. Hereditary governance protects the land and water.

We stand around the fire and speak to the ancestors. Offer our songs in Wet’suwet’en, Tahltan, Gitxsan, Tlingit. I sing the song that came to me as I was sitting by the river, watching the parade of white CGL trucks roll past. The daily invasion. Óoxjaa. The wind. The wind hits in gusts. Wuduwanúk. It is blowing. Át ayawashát. Our ancestors speak through us. The wind is changing.

Print Issue: Summer/Fall 2019

Print Title: Our Ancestors Speak Through Us